Since the end of World War II, debates have raged about the effectiveness of American armored fighting vehicles (AFVs) in that conflict. AFV aficionados tend to favor the larger, more heavily armed and armored German tanks, while deriding America’s Sherman tanks as thinly armored and under-gunned.

No doubt, the German Tiger and Panther tanks are particularly impressive—visually and in the potential outlined by their pure factory specifications. From 1943-1945, German firepower and armor protection were unequaled. Even so, I’m one of those historians that likes to point to the scoreboard. Despite all the Monday morning armored quarterbacking, American AFVs were war-winners, driven to victory by some the finest fighting men our nation has ever produced.

Inside the tanks, tank destroyers, self-propelled guns, armored cars and halftracks were crews of flesh and blood. Even though they normally rode into battle aboard a giant armored machine, there were times when the men’s small arms were critically important, too. Beyond the armored crews’ main gun, be it 37 mm, 75 mm, 76 mm, 90 mm, 105 mm or 155 mm, something as small as a crewman’s pistol could make the difference between life or death.

It is important to note that American tanks were initially designed as infantry support vehicles. The U.S. Army had a separate tank-destroyer doctrine and specialized vehicles allocated to fight tanks. They were engineered for fast and affordable mass production, and they were built to a size that could be easily transported from the USA to a distant combat zone. Soon after U.S. armored units entered combat, the lines between “tank,” “tank destroyer” and “self-propelled mount” were quickly blurred. Regardless of what they road into battle, crews needed to understand how to support the G.I. infantry, fight enemy tanks and act as anything from snowplow to ambulance.

Men Of Armor: A Sacrifice In Flesh And Blood

More than 6,000 American tanks and tank destroyers were lost in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) alone. In the final accounting, the combat law of averages was not kind to the more than 12,000 U.S. tank crew casualties. For example, every time an M4 Sherman (five-man crew) was penetrated by a German anti-tank weapon, one crewman was killed and another one seriously wounded. Tanks that caught fire suffered more casualties than those that didn’t.

And while the German 88 mm anti-tank guns made headlines and were always on the minds of American tankers, the Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck hollow charge anti-tank rocket/grenade launchers were particularly dangerous to tank crews—in the last year of the war, these short-range, infantry weapons were responsible for 21 percent of all American vehicle crew losses. And for all those tankers killed and wounded inside their vehicles, an even greater percentage became casualties when they bailed out. There was a critical need for useful small arms for the tank crews when they were outside their vehicles for any reason in the combat zone.

There was much for a tank crew to know—simply keeping their vehicle’s mechanical systems in good order was a full-time job—an immobilized tank was of little value. Beyond the automotive components was the armament, and the main gun and onboard machine guns needed regular maintenance. New crewmen not only needed to learn complexities of the vehicle and its weapons, but they also had to be able to perform as infantrymen on certain occasions.

The U.S. Army publication “Combat Lessons,” published in the summer of 1944, advised:

“Be Ready for the Infantry Role. The advice concluded with “Tankers should be familiar with all infantry weapons. Sometimes it is necessary for them to fight as infantrymen from foxholes and slit trenches.”

Most American armored vehicles had provision for at least one submachine gun and a few hundred rounds of ammunition. At the beginning of the war, this normally meant a .45-cal. M1928 Thompson SMG—and interior racks and stowage were added to provide the crew with a personal defense weapon. As armored combat progressed into Italy during late 1943, many tank crews gave up most (if not all) of their stowed Thompson guns in favor of more “ready” ammunition storage for the main gun or the internally mounted machine guns. The Thompson was powerful and reliable SMG, but at 32″ long, it was difficult to maneuver in and out of the tight tank hatches.

By the time of the D-Day invasion, a pair of new small arms became available to the tankers—the folding stock M1A1 carbine, and the collapsing stock M3 .45-cal. submachine gun (the “Grease Gun”). Unfortunately, almost all the M1A1 carbines were issued to paratroopers, and at first, so were many of the M3 SMGs. The Grease Gun would replace the Thompson and become the most common SMG in the hands of tankers during the last eight months of the war.

The M3 SMG provided .45-cal. firepower in a small package (less than 22″ with the stock collapsed), highly valuable in the tight confines of a tank. The official history of the 101st Cavalry Group (Mechanized) describes how potent the M3 could be when needed:

At Meckendorf, Germany: “the Command Post door was blown in with Panzerfaust fire and then they came through the windows screaming, “SS,” and the darkened room lighted momentarily from the muzzle blast of a roaring “grease gun.””

The Bail-Out Conundrum

The safest place for a tanker was inside his vehicle. That is, until the moment it was hit, the armor penetrated, and the tank caught fire. In that case, the crew had only a few seconds to bail out, squeezing themselves through tight hatches in a frenzied moment of extreme panic. There was little chance the crew had the time to grab a weapon and extra ammunition. Even so, once outside the tank, the men were suddenly without armor plated protection, and too often, they had nothing with which to defend themselves. In these situations, the M1911 pistol was the firearm that made the most sense—a handgun that could be worn any time the crew was in combat. However, the smallest gun in America’s armored arsenal also presented size problems of its own.

An August 1944 report from the 702nd Tank Battalion in France states:

“In tank casualties of this unit and from information gathered from other units, each tank has burned when hit and does not permit personnel to evacuate any equipment other than that carried on the person. Therefore, it would be a great savings to the Government and afford future protection to the personnel for the individual arm of each tank crew member to be the automatic pistol with shoulder holster, in lieu of the Thompson submachine gun as now authorized. It is highly desirable however that one (1) submachine gun M3 be an integrated part of the equipment of the tank.”

Officers of the 702nd Tank Battalion commented in a November 1944 after-action report:

“The automatic pistol should be the individual arm for all tank crews.” Also, “paratrooper-type” first aid packets should be issued as most tankers have discarded their pistol belt and now carry a first aid packet in the pocket.”

The traditional pistol belt with its bulky hip holster had been discarded, because it tended to snag on hatches and other tank equipment. The tank commanders of the 702nd also agreed that the Thompson SMGs remaining in their vehicles should be replaced: “Recommend item be replaced with Pistol, Caliber .45, and shoulder holster.” As noted in their earlier comment, most tankers discarded their standard pistol belt as the M3 and M7 shoulder holsters were preferred. But the U.S. shoulder holsters did not have a pocket for a spare magazine, so any additional ammunition for the M1911 pistol had to find space in pants, coveralls or jacket pockets.

Eighty years later, the perfect “personal defense weapon” for America’s tankers is still elusive. The best place for a tanker remains his own tank, provided everything is in working order. Colonel C. B. DeVore, of the 1st Armored Division offered this advice in case a tank was disabled: “In the event a tank becomes a casualty, the infantry should protect it until it can be evacuated. The crew of a disabled tank should continue to render fire support as long as its armament functions and ammunition lasts.”

The Browning Machine Guns: Secondary Armament Of Primary Importance

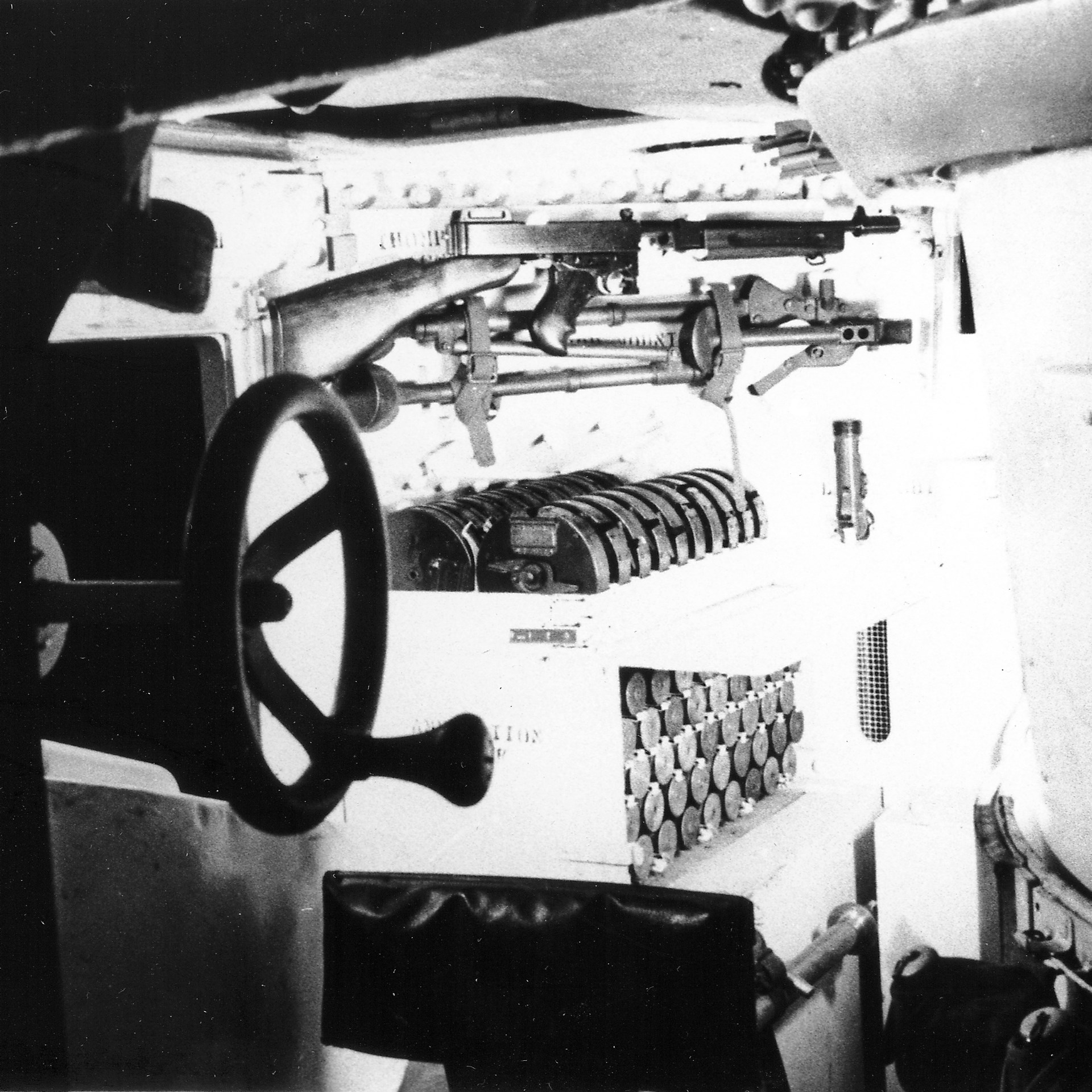

Along with their main gun, American tanks were equipped with a potent mix of Browning machine guns. In the bow and coaxial positions was the “A5” variant of the .30-cal. M1919. Browning M1919A4s or A5s were also carried on the turret roof on an anti-aircraft mount. Mounted atop the turret on the M4 Sherman medium and M26 heavy tanks, along with most tank destroyers and self-propelled guns, was the .50-cal. Browning M2 machine gun. Initially intended for anti-aircraft defense, the big Browning became almost as important as main gun in certain situations.

General Bruce C. Clarke of the 4th Armored Division commented on the Browning M2 .50 Caliber machine gun: “I told my men that the greatest thing on a tank was a free .50 Cal. MG in the hands of the tank commander … ”

Atop the M4 Sherman, the .50-cal. was initially mounted ahead of the commander’s hatch. Later variants saw the heavy MG relocated to the rear of the turret, requiring the gunner to stand on the engine deck to operate the weapon. Tank crews placed such great value on the .50-cal. MGs that multiple modifications were made to their mountings, and even an extra crew member was added to use the big Browning. A company commander from the 67th Armored Regiment (2nd Armored Division) described their solution in “Battle Experiences”:

Caliber .50 Machine Gun On Medium Tank:

-

- Six-man crew in our medium tanks with the 76mm gun: “We use a sixth crew member to fire the .50 caliber machine gun. He rides standing on the loader’s seat and assists the tank commander by watching for targets on the left flank. He interferes very little with the loader and may even help with the loading.”

- Uses and results: “The .50 caliber is used against enemy anti-tank guns and half-tracks as well as personnel, in one case we knocked out a moving halftrack at 1500 yards. The enemy fears this gun, particularly when incendiaries are used.”

- Ammunition rack: “A rack that holds 12 boxes of .50 caliber ammunition has been built on the rear of the turret where the gunner can reach the ammunition without help from other crew members.”

Some crews of the 35th Tank Battalion (4th Armored Division) brought the power of the .50-cal. guns to the coaxial position in the turret: “We salvaged some airplane .50 caliber machine guns and mounted them coaxially in place of the .30 caliber gun on some of our medium tanks. We like them because they fire faster, have more punch, and the Germans fear them.”

The Germans did fear the .50-cal. MGs, and rightly so. When it came to the Browning M2, the greatest challenge for the tankers was finding space for the hefty .50-cal. ammunition. Fortunately, the Browning .30-cal. MG was a readily available and fully adequate substitute.

Tank commanders of the 702nd Tank Battalion compared notes on the .30- versus .50-cal. machine-gun debate in a report dated Nov. 16, 1944:

“There is a varied opinion on the desirability of the .50 caliber machine gun as a coaxial or anti-aircraft gun. It is felt that for “ranging-in” purposes, the .50 caliber would be better than the .30 caliber, however, with consideration of ammunition expenditure and available storage space for ammunition, the .30 caliber gun remains the more desirable of the two.”

In the April 1944 Report of the New Weapons Board, several tank commanders that had fought in the Italian campaign offered their recommendations for upgrades and modifications to the machine guns of the M4 Sherman tanks:

Machine Guns:

-

- The bow machine gun is much used in combat operations, although all crews agree that this weapon is extremely hard to fire accurately and would like some means of sighting to be provided. As it is known that the tanks draw fire and that the bow machine gun is never used unless the position of the tank is known to the enemy, it was suggested that, to improve accuracy of fire, the percentage of tracer rounds be increased to 50 or 100 percent.

- Crews exercise extreme care in preparing Cal. .30 ammunition for the two machine guns; as a result, stoppages seldom occur except when the tanks have operated for a considerable distance before the ammunition is used.

- Crews report that accurate collimation of the coaxial gun with the periscopic sight is generally impossible; therefore, the mount which permits accurate adjustment of the coaxial machine gun will be welcomed.

- At present, the anti-aircraft machine gun is not considered essential in Italy. It should be realized, however, that in this command the Allied forces have complete air superiority. A mount for the Cal. .50 machine gun that would permit firing at ground targets with ease is desirable.

Even though the tanks could carry far more machine gun ammunition than the G.I. ground-pounders, those extra rounds could be quickly spent. Consequently, there was a delicate balance between useful “recon by fire” and wasteful shooting. The summer 1944 edition of the U.S. Army’s “Combat Lessons” emphasizes this tip to tankers:

“When operating tanks without infantry or light tanks in front of you, don’t be afraid to fire both your main gun and your .30-caliber guns at what might be a likely enemy position. A .30-caliber machine gun on the anti-aircraft mount comes in handy; it can be operated more easily than the .50-caliber and allows the tank commander to stay lower in the turret as he is firing it. The more plentiful supply of .30 caliber ammunition is an additional advantage. However, ammunition is not always as plentiful as it may seem. It does not take a tank long to burn up several thousand rounds of machine gun ammunition.”

To that point, while the tanks were supporting infantry the use of the bow machine gun was very important, but the extremely limited view of the bow machine gunner made for difficult work in the fog of war. The 12th Army Group’s report on their battle experiences in Normandy explained:

“Caution comes from the VII US Corps that when tanks are working closely with infantry, great care must be exercised in using the tank’s bow gun. Its low position and other characteristics make it a serious hazard to infantry who may be in front of the tank.”

In the final accounting, America’s World War II tankers were very well equipped with the weapons needed to smash through Axis forces on the road to final victory. In the end, it was the iron will of American tank crews that made critical difference.

Belton Cooper’s magnificent book “Death Traps: The Survival of an American Armored Division in World War II” (Presidio Press 1998) describes a remarkable action in the spring of 1945, a tank versus infantry battle worthy of an epic movie scene.

“In the fighting around Hastenrath and Scherpenseel, the tanks, without adequate infantry support, performed almost superhuman acts of heroism to hold on throughout the night. It was reported that one of the tankers, in his tank on a road junction, was the only surviving member of his crew but was determined to hold his position at all costs. A German infantry unit approached, apparently not spotting the tank in the darkness. The lone tanker had previously sighted his 76mm tank gun down the middle of the road. He depressed the mechanism slightly and loaded a 76 mm HE. As the Germans advanced in parallel columns along each side of the road, he fired. The HE shell hit the ground about 150 feet in front of the tank and ricocheted to a height of about three feet before it exploded.

“The shock took the Germans completely by surprise. The American tanker continued to fire all his HE shells as rapidly as possible, swinging the turret around to spray the German infantry, who were trying to escape into the fields on both sides of the highway. Loading and firing the gun by himself was extremely difficult, because he had to cross to the other side of the gun to load and then come back to the gunner’s position to fire.

“After exhausting his HE and .30 caliber ammunition, he opened the turret and swung the .50 caliber around on the ring mount and opened fire again. He continued firing until all of his .50 caliber ammunition was exhausted, then grabbed a .45 caliber submachine gun from the fighting compartment and opened fire again. After using all the ammunition from his Thompson and his pistol, he dropped back into the turret and closed the hatch and secured it.

“He opened his box of hand grenades and grabbed one. When he heard German infantry climb onto the back of the tank, he pulled the pin, cracked the turret hatch slightly, and threw out the grenade. It killed all the Germans on the back of the tank and those around it on the ground. He continued to do this until all his hand grenades were gone; then he closed the hatch and secured it.

“By this time, the German infantry unit apparently decided to bypass the tank. From the vicious rate of firing, they must have assumed that they had run up on an entire reinforced roadblock. When our infantry arrived the next day, they found the brave young tanker still alive in his tank. The entire surrounding area was littered with German dead and wounded. This, to me, was one of the most courageous acts of individual heroism in World War II.”

Read the full article here