“Three oh eight Winchester.” “Twenty-six Nosler.” “Seven point eight two Warbird.” “Twenty-two Eargesplitten Loudenboomer.” “Thirty-three Poacher’s Pet.” “Two-forty Page Super Pooper.” Even novice riflemen or cartridge enthusiasts will recognize the former two chamberings, but as for the latter four, only the obsessed will likely have knowledge of them. And yet, all reveal a feature of the cartridge and/or the designer in their naming convention. Shotshells are no different; gauge and length designations tell us much, though the origins of such are often lost on many of today’s users.

Ammunition is unique in that designations oftentimes convey critical information, while in other instances, they’re simply stroking the ego of the designer(s)—and there are untold instances of both. While tacky tags serve little purpose for most riflemen other than fodder for podcasts and campfire clashes over cartridge superiority, it can be baffling for novices. Worse yet, getting it wrong—as in using the incorrect ammunition—can have dire results. Let’s look at some of the mixed-up monikers for metallic cartridges and shotshells, as well as the baffling system of measuring weight.

Metallic Cartridges

Until relatively recently, European and Asian cartridge designers (military or otherwise) named their cartridges in a straightforward and sensible manner; that is, they had designations matching their dimensions, such as 6.5×55 mm Swede (bullet diameter and case length), 6.5×47 mm Lapua, 7×57 mm Mauser and 7.5×54 mm French. Oftentimes the country of origin or configuration (i.e. “R” for rimmed) accompanied the dimensions. Examples of this include: .303 British; .43 Dutch Beaumont; 6.5×50 mm Japanese; 7.62×54 mm R; and 8×50 mm R Austrian Mannlicher.

It becomes a muddled mess, though, when the cartridge name isn’t telling of an important attribute, such as bullet diameter. Here’s a case study in confusing: The 8×57 mm R 360 and 8×57 mm J Mauser fire 0.318″-diameter bullets. The 8×57 mm JS, however, uses 0.323″-diameter projectiles and is loaded to higher pressures. According to the Cartridges Of The World, 13th Ed., “This cartridge is now universally called the 8×57 mm Mauser, or simply, the 8 mm Mauser, and has caused considerable historical confusion.” We’re not done yet; there’s also the rimmed 8×57 mm R JS Mauser, which debuted in 1888 with 0.318″ bullets but was adapted in 1905 to 0.323″ projectiles. Puzzling, right?

While newer European cartridges are recognizable abroad by their dimensions, foreign companies have read the playbook of American makers. Take the .338 Lapua Mag. for example. Its designation details the bullet diameter and the Finnish maker that saw the cartridge through its final development and standardization. The stately .308 and .358 Norma Mag. cartridges are also named for their bullet widths and the company that designed them. The .338 Norma Mag., though, curiously originated with wildcatters.

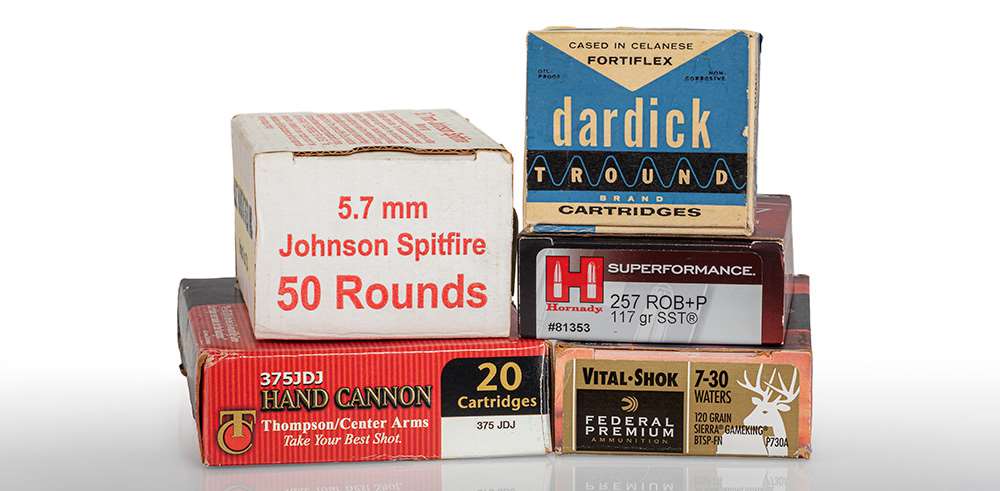

Cartridge names are often seen on headstamps (l.) and can highlight speed, as with the .221 Fireball, .220 Swift and .219 Zipper (1.), evoke grandiose imagery, as with the .338 Excalibur, .300 ICL Grizzly and 7.21 Firebird (2.), or pay homage to their developers, as with the .458 Lott, .416 Taylor, .35 Whelen and .220 Howell (3.). Box labels (above) likewise extol the cartridges’ virtues and provide such useful information as bullet weight and type, velocity and suggested applications.

New European cartridges are somewhat of a rarity, especially when compared to the United States, where, even during “ammunition shortages,” companies still manage to keep the conveyor belt of new creations churning. If there’s an untapped niche, someone will find it. Can’t find one? Create it.

America wasn’t always over the top when naming cartridges. For instance, at the debut of the timeless .30-30 Winchester in 1895, “the original loading used a 160-gr. soft-point bullet and 30 grains of smokeless powder, thus the name .30-30 for a .30-caliber bullet and 30 grains of powder,” explained the abovementioned book. Similarly, the original .45-70 Gov’t (45-70-405)—featuring a .45 caliber, 70 grains of blackpowder and a 405-grain bullet—adopted in 1873 in the single-shot “Trapdoor” Springfield rifle, had a label that made sense. Fast-forward to 1906, with the adaptation of the .30-’03 into the “Cartridge, ball, caliber .30, Model of 1906,” now more widely known as .30-’06 Sprg.

At times, manufacturers used velocities to hawk cartridges, and these ended up in the cartridge monikers. As an example, when the .250 Savage was introduced in the Savage Model 99 lever-action rifle, its first loading featured a .25-cal., 87-grain bullet propelled to 3,000 f.p.s.—hence the name .250-3000. While that was a real feat in 1915, the speed of the subsequent 100-grain offering nearly two decades later wasn’t so spectacular, so the name henceforth became .250 Savage. Similarly, the .220 Swift, which was developed by Winchester and debuted in 1935, was the first mainstream cartridge to break the 4,000-f.p.s. mark. The recent .223 WSSM does the same. Speed sells. By the way, the .250 Savage uses a 0.257″ bullet, while the .220 Swift and .223 WSSM both utilize 0.224″ projectiles.

Back to the .250 Savage for a moment. That cartridge and others wouldn’t be left alone. P.O. Ackley, a renowned author, barrelmaker, gunsmith and tinkerer, as well as other “wildcatters,” decided good enough wasn’t actually good enough. Ackley, in particular, “improved” many chamberings by reducing the body taper and steepening the shoulder angle. Why? Besides increasing case life and powder capacity for increased velocity, the treatment reduced the need for case trimming significantly. Best of all, in an Ackley chambering, the parent case can be used as normal, and the firing process fire-forms the case to the new dimensions. Such cartridges are known as “Ackley Improved,” and the .250 Savage is one of them. Actually, I believe that the .250 Savage Ackley Imp. is the best of the bunch, but I’m biased.

Lysle Kilbourn created the .22 K-Hornet in 1940. Similar to Ackley’s process, the blown-out, fire-formed case offers a marked performance increase, as well as better case longevity, than the parent. Few “improved” cartridges ever go mainstream, however, in 2007, Nosler registered the .280 Ackley Imp. to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI), making it a factory offering. Its popularity has only grown since then.

Creating a cartridge need not be difficult; budding wildcatters simply need to wait for an inevitable new chambering to debut and then either neck it up or down—usually with little or no other modification. Look at recent cartridge introductions for proof.

Many new cartridges are designed as described above—the existing cartridge is simply adapted to accept a different bullet diameter. Examples include: .25-’06 Rem.; 6.5-284 Norma; 6.5-300 Wby. Mag.; .30-378 Wby. Mag; and .338-378 Wby. Mag. Although the names of the former duo denote the new caliber and parent, the latter trio only partially do. While the 6.5, .30 and .338 are indeed the new bullet diameters, the parent case, the .378 Wby. Mag. uses 0.375″-diameter projectiles. But three-seventy-eight sounds better, right? Sure does. Clever marketing.

Nomenclature Narcissism

Cartridge designers frequently want you to recognize their contribution to the shooting world. Here’s evidence. How about the .14/.222 Eichelberger Mag., the entire Weatherby series, .224 Clark, 6 mm Dasher, .270 Ren., .270 Gibbs, 7 mm JRS, .30 Herrett, .308×1.5-inch Barnes, .327 Martin Meteor, .338/50 Talbot, .35 SuperMann, .358 UMT (Ultra Mag Towsley) and .416 Aagaard, to name a few. Note that most are wildcats (i.e. not SAAMI approved), and that the designer’s name—usually the surname, but full legal name at times—is on full display.

Cartridge names such as (clockwise from upper r.) Dardick, Roberts, Waters, JDJ (J.D. Jones) and Johnson honor their developers.

Inspiration can be found nigh anywhere. Some creators look to mythology, such as for the .224 Valkyrie, 6.5 mm Grendel, .300 Pegasus, .338 Excalibur or .50 Beowulf, while others look to the heavens. Two notables are the 9.53 Saturn and 10.57 Meteor. Entomologists will approve of .14 Eichelberger Bee, .14 Walker Hornet, .22 Hornet, .22 Taranah Hornet, .219 Donaldson Wasp, .218 Bee or .218 Mashburn Bee, while the .25-222 Copperhead and .450 Bushmaster should strike a chord with herpetophiles. Feline aficionados should welcome the 6 mm Cheetah or 6.5 Leopard wildcats, and bird lovers cannot resist the .250 Mashburn Falcon, 6.71 Blackbird or the Hawk line of cartridges. Need cute? There is the .10 Eichelberger Pup, 5.5 mm Velo Dog, .17 Javelina and .17 Squirrel.

Fans of dino flicks will appreciate the .257 Raptor and .577 Tyrannosaur, while those with an interest in the supernatural will want to check out the .255 Banshee, 6.71 Phantom, .338 Spectre or .500 Phantom. The 7.21 Tomahawk, 360 Buckhammer and .450 Bonecrusher are attention-getters. So, too, is the .358 Gremlin, but I’m not too sure that I trust that name. Geography is covered with the Creedmoor and Alaskan series, along with the .35 Indiana, .375 Canadian Mag. and .500 Wyoming Express. The .17 Flintstone Super Eyebunger should make you scratch your head, as should the .17 Pee Wee and .219 Zipper. Certainly the .240 Page Super Pooper takes top honors for creativity.

“Precision” is today’s buzz word in all things rifle-related. Don’t believe me? Then explain Hornady’s Precision Rifle Cartridge (PRC) family of cartridges. The “red machine” also has the ultra-efficient and AR-platform-capable Advanced Rifle Cartridge (ARC) chamberings. Again, not a lot to go on, but better than the 8 mm PMM (Poor Man’s Magnum). You can always call your cartridge a “Legend” at its debut, as did Winchester with its 350 and 400—predestination at its finest. Before moving on from the nonsensical naming conventions, we need to give a shout-out to employers, including the Shooting Times series (though I readily use the 7 mm STW). And who could ever forget the .45 Trump for our 45th, and now 47th, president. Happenstance? I think not.

Upping The Ante

If naming a cartridge after an oversized lizard or mythical creature doesn’t make things confusing enough, misidentifying the bullet diameter will assuredly do it. And .30-cal. cartridges are the worst offenders.

Most .30-cal. cartridges use 0.308″-diameter bullets, but save for the .308 Win., .308 Marlin Express and .308 Norma Mag., this is seldom reflected in the cartridge’s name. Instead, it’s simply “.30,” such as .30-30 Win., .30-40 Krag, .30-’06 Sprg. and .30 T/C, to name a few. Worse yet, in the past, when cartridges were branded “magnum,” that .308 suddenly became .300. Examples include: .300 H&H Mag.; .300 WSM; .300 Win. Mag.; .300 Wby. Mag.; and .300 RUM. Although not marketed as a “magnum” cartridge, this trend continues today with the .300 PRC.

Cartridges are often named after firearm and ammunition manufacturers, too, such as the .444 Marlin, .375 Ruger and .338 Lapua Mag. seen here.

What’s a “magnum?” I’m glad you asked. The NRA Firearms Sourcebook defines it as “a term commonly used to describe a rimfire or centerfire cartridge, or shotshell, that is larger, contains more shot or produces higher velocities than standard cartridges or shells of a given caliber, or gauge.” So any cartridge that “produces higher velocities than standard cartridges” qualifies. Consider that for a moment. It’s easy to tack that title onto nearly anything. But, in bygone days, the now-abhorred belt had to be present. The Winchester Short Magnum (WSM) and Super Short Magnum (WSSM) examples, as well as Remington’s Ultra Magnum (RUM) and Short Action Ultra Magnum (RSAUM) cartridges, were early modern ones to buck the trend, as they were true magnums devoid of belts.

Shotshells

Shotgun nomenclature is more straightforward than it is for metallic cartridges. Outside of the .410 bore, which is a measurement of diameter, shotguns are referred to by gauge. Preceding “gauge” is a number that relates to the quantity of lead balls of that bore diameter (i.e. width) that are required to equal one pound. For instance, the ubiquitous 12 gauge, which has a SAAMI-specified bore diameter of 0.725″ + 0.020″, requires a dozen lead balls to equal that weight. Therefore, the larger the bore diameter, the fewer lead spheres and vice-versa. Other than the aforementioned 12, popular gauges in America include the 10, 16, 20 and 28, and there exists a smattering of 32s and 34s as well. So, although it’s counterintuitive, the 10 gauge is bigger than gauges larger in number, such as the 16 and 20. Also strange is the fact that, outside of the 3½” 12 gauge, sub-gauges have some of the highest SAAMI-established maximum average pressures (MAP); in fact, the new 3″, 28 gauge has a 14,000-p.s.i. MAP, while that for the 3″ .410 is 13,500 p.s.i.

Shotshell length is established when unfurled (pre-crimped), and most gauges use 2¾” shells as standard. Yet again, the .410 is the one-off; its standard shell measures 2½”. What’s more, of the popular gauges (10, 12, 16, 20, 28 and .410 bore), only the 10 and 16 gauges are unavailable in a 3″ offering. Meanwhile, the 10 and 12 gauges have 3½” variants for those demanding maximum payloads and accepting of their punishing recoil. Sub-length shells can be found in several gauges, but none are as short as the 1¾” Aguila Mini-Shells in 12 and 20 gauge, and Federal’s Shorty Shells in the former.

Concerning projectiles, you can have “fine shot,” “buckshot” and “slugs”—or some combination thereof. Let’s focus on the former duo. Want No. 2s? Do you want 0.146″- or 0.270″-diameter pellets? Both are 2s; the first dimension refers to “fine shot,” while the latter denotes “buckshot.” Confused? I bet. And we’re just getting started.

Depending on the source, fine shot is available in sizes ranging from No. 1 to No. 12. As with shotgun gauges, the numbers are inverse in size to what’s expected, meaning No. 12s are much smaller than No. 1s. The same applies to buckshot, which, according to Ballistic Products, Inc., ranges in size from B to 0000 (quad-aught buck). Increasing in size are: B; BB; BBB; T; TT; F; No. 4; No. 3; No. 3.5; No. 2; No. 2.5; No. 1; No. 1.5; 0; 00; 00½; 000; and 0000. Some shotgunners consider 0.440″-, 0.490″- and 0.500″-diameter round balls to be buckshot, too.

Shot sizes (top, l. to r.) and their inversely numerical designations include: Nos. 81/2, 8, 71/2, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 fine shot; then B, BB, BBB; Nos. 4, 3, 1; and 0, 00 and 000 buckshot. Shotshells come in a wide variety of lengths in various bore and gauge designations, and their hull colors can be a clue to the latter (above).

Shotshell boxes used to identify “dram equivalent,” which the NRA Firearms Sourcebook defined as “[an] accepted method of correlative relative velocities of shotshells loaded with smokeless propellant to shotshells loaded with blackpowder.” Thankfully, that’s no longer the case. Instead, the actual velocity of the shells is denoted. Other than firearm functioning (semi-automatic), felt recoil and, perhaps, report, the amount of propellant needed to safely hit a specific velocity with a given payload is a moot point, which is why “dram equivalent” is gone.

I wish the same held true of “high-brass” shells. Whereas elevated brass once signified “magnum” loads, due to the brass preventing burn-through of paper hulls, that’s a non-issue with plastic hulls—and it has been for decades. But manufacturers continue to use them because that’s what consumers expect—pure marketing and waste.

Propellants & Weights

Since this article covers confusing ammunition nomenclature and related practices, it’s prudent to also discuss powders. While blackpowder and its suitable substitutes are volumetrically measured for muzzleloaders, smokeless propellants for firearms are measured by weight—in either grains or grams. Seven-thousand grains equal one pound, so 437.5 grains equal an ounce.

Bullets for metallic cartridges and muzzleloaders are expressed—in the United States—in grains, such as the Nosler 150-grain Ballistic Tip. Excluding slugs, shotshell payloads are conveyed in ounces. Slug weights are generally identified in ounces, but they can be denoted in grains, too.

Americans tend to gravitate to specific, traditional weights. Need an example? One only needs to look at the grand .30-’06 Sprg. What are the most-used bullet weights? One-hundred fifty, 165 and 180 grains, as well as the oddballs that still stick to the 220-grain round nose—count me among them. The same applies to the .270 Win.; generally, bullets are available in 130-, 140- and 150-grain weights, though Nosler has the hefty 160-grainer.

Fortunately, times have changed, and rather than the status quo, new bullets can end up where they end up, weight-wise. For instance, Berger Bullets has the 6.5 mm 153-grain Long Range Hybrid Target and 156-grain Elite Hunter, as well as 7 mm 195-grain Elite Hunter and .30-cal., 155.5-grain FullBore Target Rifle Bullet. And Berger isn’t alone.

It’s Up To You

The next time you’re scanning the ammunition shelves or shopping online, take note of the unique nomenclature associated with metallic cartridges. In all likelihood, it provides little, if any, information about each cartridge’s dimensions—especially if it’s modern and designed in America. Shotshells are a little easier to discern, as the gauge, length and payload—printed on the box—avoids the purposeful panache of metallic cartridges. If there’s a takeaway here, other than the ludicrous naming conventions, it’s that it is up to you, the consumer, to ensure ammunition/firearm compatibility and load suitability for the task, among other things. The more you know, the better.

Read the full article here