(Continued from Part 4.)

3 – Growing Food When Lives Depend On It

In addition to industrial-scale emergency forging, growing food should be started ASAP by the local community after most T2Es.This is the 2nd Tactic. 2nd Tactic: As early as possible in an emergency start a neighborhood/community-wide food growing effort that aims to swiftly create a calorie surplus. The calorie density and volume of garden/farm crops is much higher than most foraged food sources. As mentioned earlier, if we do not have sufficient local water resources don’t try this. We will fail. Crops need lots of water to grow and if our water comes from too far away or too deep below( requiring electric pumps) then we can no longer grow adequate amounts of food in our area. As was mentioned before, if a T2E happens and we don’t have abundant water resources, relocating to a place that does is one of our highest priorities.

If the emergency happens outside of our normal growing season we still have options. There is plenty that can be done to start growing food faster. In the following growing section, I will mention several resources and methods that could be used to build emergency greenhouses for growing food outside of normal growing seasons. Our modern resources might be based on a fragile foundation but our lives are filled with modern, everyday, wonder materials that can creatively be repurposed in an emergency to save our lives. Every growing idea below will focus on speed and repurposing existing resources to feed as many people as possible. An event like this will require a full-court press and a “no-huddle offense” level of effort to have a chance at getting food to people’s tables in time to save lives.

Most of the US population are not farmers and only slightly over 30 percent of US households grow a garden for food. Even fewer have the knowledge of how to grow abundant food sources without modern technology. The great news is that there is a group of people who do have this knowledge or are actively seeking to learn it, preppers like you and me. The truly prepared can be great leaders if they are willing and ready to lead in an emergency. Why prepare for possible dark days if we are not at least hoping to make it brighter with our efforts. Let’s consider how we could lead a neighborhood in an emergency food-growing effort.

The first thing to consider is how quickly we can go from planning crops to harvesting them. Iowa State University has a great list with this info. Vegetables like radishes and mustard greens can produce in as little as 30 days but they are very low in calories. Peas, cucumbers, peppers, beets, summer squash, turnip, and beans are in the 80-day range. Potatoes, melons, pumpkins, tomatoes, winter squash, corn, carrots and soybean are in the 95-day range. Grains like rye are in the 135-day range. Spring wheat in the 115-day range and winter wheat is in the 215-day range. Barley is a fast-growing grain that is in the 75-day range and amaranth is in the middle at the 90-day range. It is important to know this because it will help us plan for when new calories will show up. Also, any crop that can be grown twice in one year will double our food production or could be grown from some of the first crops’ seeds. This would be critical if land, water, or seeds are limited.

Another critical factor is how many calories we can grow in an acre; an acre is 208.71 feet by 208.71 feet or 43,560 square feet. Here are a couple good links for calories per land area: Calories Per Acre Link 1 and Calories Per Acre Link 2.

High calorie crops like potatoes, sweet potatoes, sugar beets, corn and soybeans are in the 6 to 9 million kcal/acre range. Wheat, barley, rye, winter squash, pumpkins, peanuts, carrots and amaranth are in the 3 to 4 million kcal/acre range. Beans, oats, sorghum, sunflowers, cabbage, tomatillos, tomatoes, and carrots are in the 2 to 3 million kcal/acre range. Quinoa, peas, and lentils would be in the 1 to 2 million kcal/acre. Kale, lettuce, radishes, cucumbers, onions and other greens are all below 1 million calories per acre. For all of these crops I am assuming home garden acres and not industrial farming acres.

With these factors and assuming the choice of growing crops will be limited in a T2E, I will assume an average calorie density of 4.8 million kcal/acre for a neighborhood growing situation when using my recommends below. 1 million kcal is about full rations for 1 person for a year. So, to feed 100 people would require working on 27 acres of land, 21 for food and 6 for the next season’s seeds and some losses. If we also assume one rookie adult gardener can work 2 acres of land by hand, our groups would need a minimum of 13.5 adults per 100 people to garden/farm and haul water as their full-time emergency job once the growing areas are ready. To prep the growing areas will take a lot more initial labor.

3.1 – How Many Seeds Are Needed For Survival Success?

Another critical question is how many seed are need to grow enough crops for our community? If we don’t have enough seeds after a T2E to feed our community, there is no point trying to build a short term community calorie bridge to a non-existent future calorie surplus.

Here is a list of how much seed is needed for different crops to plant 1 acre:

Corn will need 10 to 17 pounds of seed per acre.

Wheat will need 75 to 150 pounds of seed per acre.

Oats will need 80 to 100 pounds of seeds per acre.

Barley will need 60 to 120 pounds of seeds per acre.

Rye will need 60 to 100 pounds of seed per acre

Beans will need 50 to 80 pounds of seed per acre.

Lentils will need 30 to 80 pounds of seed per acre.

Peas will need 50 to 150 pounds of seed per acre

Soybeans will need 50 to 60 pounds of seed per acre

Carrots will need 2 to 4 pounds of seed per acre

Tomatoes will need 1 to 2 ounces of seed per acre

Tomatillos will need 2.5 to 3 ounces of seed per acre

Cucumbers will need 2 to 3 pounds of seed per acre

Summer Squash will need 3 to 4 pounds of seed per acre

Winter Squash will need 2 to 3 pounds of seed per acre

Mammoth Grey Stripe Sunflower Seeds will need 7 to 9 pounds of seed per acre

Sorghum will need 8 to 10 pounds of seed per acre

Seed Potatoes will need 1600 to 1800 pounds per acre

True Potato seeds will need 1.5 to 2.5 oz of seeds per acre

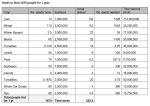

The table below is an example of what would be needed to grow a 1-year supply of food for more than 1,000 people. I have focused mainly on seeds that are edible and have a good shelf life so they can serve a dual purpose. In normal times, most of these seeds could be used as raw ingredients for the food we would eat throughout a year or two but used as crop seeds in an emergency. This also assumes the crops would grow 2,300 calories per day per person with the rest of the harvest to be saved for future planting. This mix of crops would have an average of 4.8 million kcal/acre.

Seeds in this quantity and type are very unlikely to be found in a typical group of 1,000 neighbors and at the local stores. They would have to be supplied with advanced preparation, so consider the neighborhood homes and seeds from stores to be a 5% to 10% surplus supply. It would be a heavy financial and space ask to have one family buy/grow and store these seeds for their 1,000 closest family, friends, and neighbors. Also, this is too much food for one family to rotate into their normal eating habits, seeds and money would be wasted over time. However, if this burden was shared by 10 families, then it is doable.

Here is a researched estimate for the 2025 costs and space requirements. Also, it would not be too hard to grow these crops in our gardens over a couple of years’ time, to reach the target pounds of seeds for each crop. I estimate in one or two seasons the cost of this plan could be reduced by two-thirds. Even if these stored seeds were not used to help grow food for 100 people close to us it would be a great resource of extra food (~645,000 kcal) or extra crops for ourselves, as barter, as a negotiation chip to earn a spot at a relocation site, or to strengthen our existing homestead community.

If we lived in a town of 30,000 people expand this group of seed ark families from 10 to 300, just 1% of the population. This approach would make our community very resilient at a low distributed cost. An effort this large could not stay a total secret but if it was put in place, we now have the real capacity to feed 30,000 people for a year. If you are great at influencing your community, tackle a larger scope like this. Maybe start a gardening prepper club to grow experience, emergency seeds, and teamwork. If your personality is not suitable to large group projects and this is the population in your area then consider moving to a smaller community.

3.2 – Seeds In Our Homes

The recommendation above or some variation would be our baseline seed supply to prevent starvation in our community. Here are secondary seed recommendations for our homes. First, would be a large variety of seeds for our personal garden or farm. They should be heirloom seeds that are open-pollinated that can reliably produce consistent crops generation after generation. If we buy hybrid seeds, they are designed to grow a specific product once and no guarantees after that if we save seeds from that first crop.

I have had some luck saving tomato, pepper, and summer squash seed from seed packs that were not reported as heirloom. They produced good second-generation crops. Maybe they were unmarked heirloom varieties or maybe luck was on my side. In an emergency I will use whatever is at hand. But if we have the choice then pick heirlooms now so we won’t have to worry about crop problems after multiple generations.

One other factor to consider is if the seeds we buy can be used for vertical gardening. A portion of our emergency seeds should be for this type of growing unless we have surplus farmland. Vertical gardening allows for growing more with fewer inputs like land, water, fertilizer, time, and energy. Additionally, vertical gardening can increase calorie yields for crops because the plant foliage is exposed to more sunlight and vining crops will keep growing and producing for more days. For example, runner beans almost always have higher yields than bush beans. The same is true with indeterminate versus determinate tomatoes; indeterminate means that a tomato plant will grow as tall as its supports and it will continue producing fruit during the whole growing season.

Crops that are good vertical plants include: summer squash, winter squash, runner beans, pole beans, melons, cucumbers, peas, indeterminate tomatoes, tomatillos, southern peas or cowpeas and pumpkins. Supports can be poles or arches holding up a metal or string mesh, ropes hanging down from a roof, chain link fences, and even other plants like corn, sunflowers, or sorghum.

We should also include a good variety of herb seeds to grow for flavor. The modern kitchen cupboard can easily be better stocked with an assortment of spices that would surpass any ancient king. We are used to experiencing many different flavors each week. During a T2E when we are living on basic survival food with bland flavors we will crave variety. We need to make a list of our favorite spices and store seeds to grow them ourselves. This can also be a great barter source to help others overcome their new flavorless diets.

After we buy some seeds we shouldn’t just tuck them away in a dark, dry, and cool place for an emergency. We should open some of them up, plant them, and harvest them to eat now and to preserve for later use.

Additionally, we will want to learn how to grow some of our crops to collect their seeds for the future. For example if we want zucchini seeds then need to let some become baseball bat-size squash to grow mature seeds. Lettuce and cilantro need to be allowed to bolt, form seed pods, and then dry out. Carrots and onions need to be grown into the next season before they will go to seed. Seed to Seed by Suzanne Ashworth is a great book to use as a physical reference or just search specific crops on the Internet and there will be loads of articles and videos on seed production.

Saving our own seeds is great for a few reasons. One, it is a valuable skill to develop now when the consequences for failure are just frustration and not life-threatening. Two, it will save us money, as we will not need to pay for seeds twice if we grow and save enough seeds. Seed costs — like everything else — are rising with inflation. Gathering and saving seeds keeps more money in our pockets. In some years, I will just grow a small amount of aging seeds to replenish my stock with new fresh seeds so I won’t have to buy them again. Third, saved seeds can be a very inexpensive but thoughtful gift to share with our family and friends.

I think one of the wonders of life is to watch a seed we planted climb out of the ground and expand to a fruit-bearing giant compared to the seed it came from. Who wouldn’t want to share this wonder with family and friends? Fourth, save extra seeds each year to create an excess that we can use to sell, barter, or give as charity to others if hard times show up. If we do this for multiple years, we will have a stock of seeds large enough to feed a small army with very little cost.

To store seeds, I have had great luck packaging fully-dried seeds in Ziploc bags with a paper towel placed inside. Don’t forget to label and date these seed packs.

We also have another supply of bulk seeds that we might not recognize, and we normally just call them food. Dried beans, popcorn, dried lentils, dried chickpeas, potatoes, sweet potatoes, quinoa, and unsalted, unroasted whole peanuts in the shells can all be planted to produce crops. I have grown plants from most of these seeds I bought at regular stores. We might even have large quantiles in Mylar bags or in #10 cans as part of our long-term food storage. For $40 to $80 we could quickly have more basic seeds than we could likely plant in our gardens for a year.

We also have another supply of bulk seeds that we might not recognize, and we normally just call them food. Dried beans, popcorn, dried lentils, dried chickpeas, potatoes, sweet potatoes, quinoa, and unsalted, unroasted whole peanuts in the shells can all be planted to produce crops. I have grown plants from most of these seeds I bought at regular stores. We might even have large quantiles in Mylar bags or in #10 cans as part of our long-term food storage. For $40 to $80 we could quickly have more basic seeds than we could likely plant in our gardens for a year.

Wheat berries can also be grown into crops and they also have a much longer shelf life than wheat that is ground into flour. If we don’t have any wheat berries we should consider adding them to our food storage. We might even have a bag of bird seed that has viable sunflower or millet seeds. A final place to look for seeds in an emergency is in your kitchen refrigerator.

Tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, melons, corn, and squash can all have their seeds collected and be used to grow crops. These will likely be hybrids that may grow a slightly different crop, but in an emergency they will grow extra calories to help run up the calorie score as high as possible. Also, in most climate zones, the bottom 1/4 of onions, lettuce, or celery can all be directly planted to regrow these plants.

A quick way to test the viability of most seeds is to put 5-20 seeds in a moist paper towel and then seal it in a plastic bag. Put that in a dark, warm place and check the seeds every couple of days. Count the number of seeds that sprout compared to the total number of seeds we are testing. This will give us a germination percentage. This will tell us how many seeds we should plant per hole to make sure we get a plant to start. If the germination percentage is low we will need to plant more seeds per hole. If no seeds sprout we will have learned that those seeds are not viable and we should not waste time trying to grow them.

3.3 – Seeds In Our Neighbors’ Homes

Our neighbors will also have many of the same seed resources as us. Start by asking them to look for old packets of seeds for their gardens. They will also have food in their kitchens that are also seeds they can grow for food. Our role would be to help them to see these sources as future crops before they are used as a meal. Most neighborhoods will likely have many pounds of dried beans and popcorn that could be used to expand our emergency garden plans. Early in an emergency, we should inventory our seed resources and use this information to plan our emergency gardens.

(To be continued in Part 6.)

Read the full article here