In 1569, Spanish explorers saw pronghorn and simply recorded them as “goats” in their journal because it was not entirely clear to them what this odd animal was. Its similarity to African antelope eventually resulted in the widespread name “Pronghorn Antelope.”

However, further evaluation revealed this was not a true antelope, but it was too late; the name had stuck. It was a buck collected in Nebraska by the Lewis and Clark Expedition in September of 1804 that finally brought this animal to the attention of science. Its scientific name, Antilocapra americana, literally means “American antelope-goat,” but to be accurate and reduce confusion, biologists refer to them simply as “pronghorn.”

The Diverse Pronghorn Family

The pronghorn is uniquely North American. Its entire evolutionary path and current distribution is solely of this continent. The first pronghorn-like ancestors appear in the fossil record about 19 million years ago. Their horns were an odd array of very diverse shapes resembling miniature moose, deer, and cattle. Some sported long, spiraled horns, forked horns, and later in the Pleistocene, there were pronghorn with two, four, and even six horns! In all, there were at least 18 different forms of primitive pronghorn, and fossils show characteristics associated with fast runners, so it appears they have been speeding through millions of years.

The pronghorn family (Antilocapridae), is grouped into 2 subfamilies: the Merycodonts and Antilocaprines. Merycodonts appeared nearly 19 million years ago, and by the time they were fading from the fossil record 9 million years ago, the Antilocaprines were rising to prominence. The horn cores of all members of this family are distinctive in that they arise from the top of the eye orbit like modern pronghorn.

Merycodonts were actually very small animals; most of the five recognized types stood only about 20 inches tall at the shoulder and weighed 25 to 50 pounds. Unlike later antilocaprines, many merycodonts retained their dew claws like deer on at least the front feet and had upper canine teeth. But, the most characteristic and diagnostic feature of merycodonts was their horns.

Rather than a straight blade-like horn core, the horns were palmated like a moose (Merriamoceros) or branched like a deer (Ramoceros). Others had a simple two-point “Y” on each side (Merycodus, Meryceros, Cosoryx, and Paracosoryx). The horn surfaces were smooth with holes for blood vessels, indicating they were covered with skin and not a keratinous sheath like today’s pronghorn. Bony rings around the bases of horns after the animal’s second year gave rise to a theory that the skin covering may have been regulated seasonally by hormones to be shed and regrown annually, leaving rings where the skin regressed. The presence of hornless merycodont skulls indicates females did not have horns.

Some of the earliest antilocaprines coexisted with the latest merycodonts, but antilocaprines were larger in body size with longer legs, and they lacked upper canine teeth and dew claws. Antilocaprine horn cores were shaped more like cones or blades, and the surface of the horn cores indicates the upper parts were covered with a sheath, while the lower base was fur-covered.

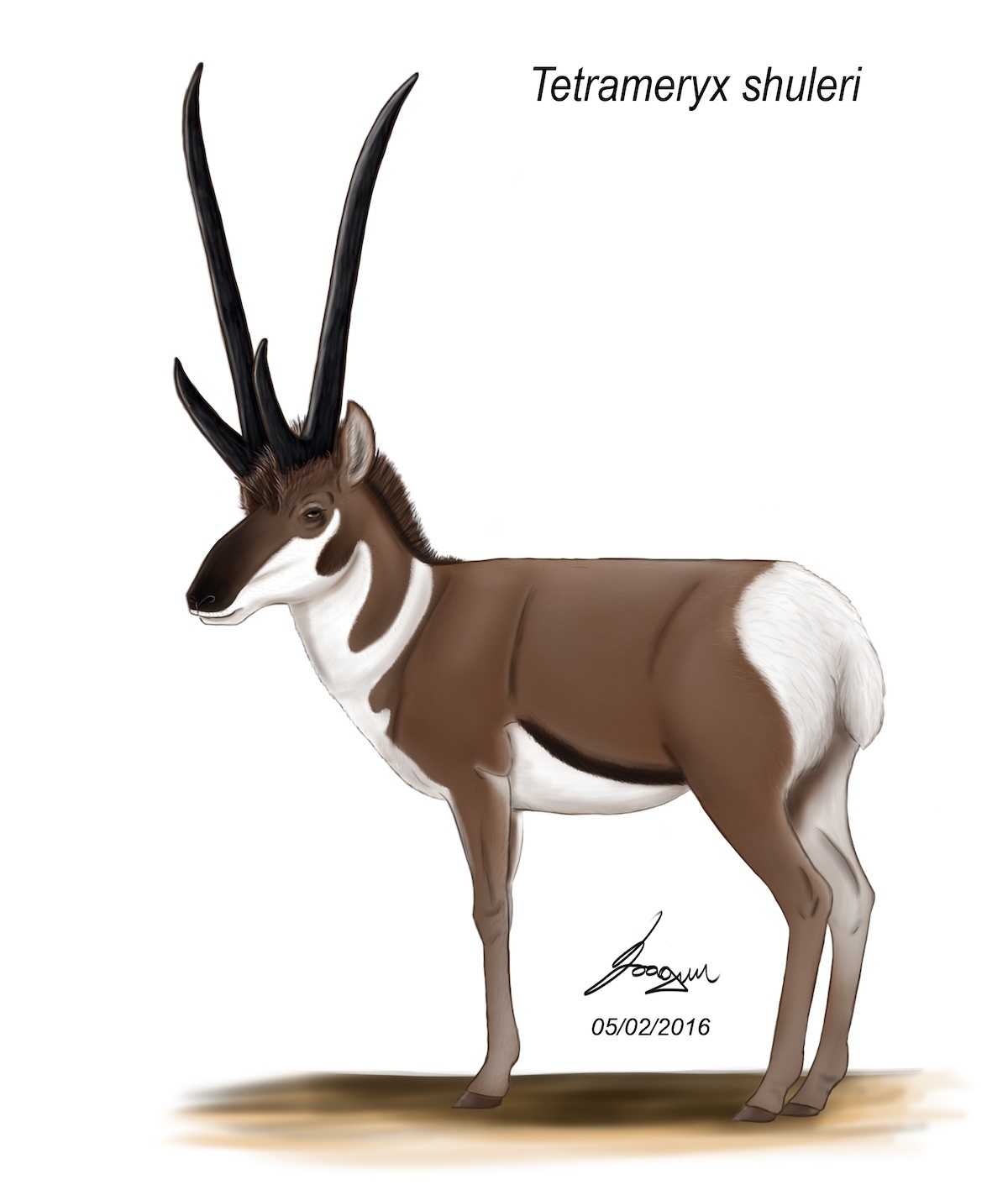

Antilocaprines varied from 6-horned specimens (Hexameryx, Hexabelomeryx), to some resembling wild bovines (Osbornoceros) and true antelope of Africa (Ilingoceros). Many forms had forked horn cores on each side (Ottoceros, Ceratomeryx, Texoceros, Capromeryx, Sphenophalos, Plioceros, Tetrameryx, Stockoceros, and Hayoceros). Unfortunately, no horn sheaths from ancestral antilocaprines have been preserved in the fossil record, so we are left to imagine what kind of elaborate sheaths would have been found on these animals. Did the 6-horned species have sheaths that all curved inward or outward? Did they have extra prongs?

The Lone Survivor

There are two kinds of animals: Extinct and Extant. Extinct animals no longer roam the earth, while those that are extant have survived the many challenges Mother Nature threw at their ancestors. Animals still with us are the survivors who were successful in running the gauntlet of evolution. Those species making it to safety at the end of the gauntlet rarely come through the ordeal unchanged, both physically and behaviorally. These changes, or adaptations, allowed some species to survive changing environments while others perished. Out of all these amazing forms of pronghorn, the only survivor is the one we now know as the American pronghorn.

Without our incredibly successful system of conservation, we would have also lost the pronghorn. In 1879, John Murphy wrote, “This interesting animal, like some others, is destined to disappear in a short time from the list of American fauna…”

Sadly, the continent’s pronghorn population dwindled from millions to about 15,000 by 1910. Restrictions on pronghorn harvest started in most states between 1900 and 1911, and within a couple decades, populations were on their way to recovery. Currently, more than a million pronghorn occupy their former haunts across a vastly different North America.

Among all the antilocaprids we know about during the last Ice Age, it is not entirely clear which is the direct descendant of today’s pronghorn. One leading candidate is the Subantilocapra because of its blade-like horn cores resembling pronghorn and because of dental similarities. Interestingly, Subantilocapra had a bony point on the leading edge of the horn core where the prong is located on the sheath of modern pronghorn.

The Evolution of Speed

The modern pronghorn survived the last Ice Age because it had the right suite of adaptations it acquired in its race through the millennia. The adaptation that pronghorn are most famous for is their speed. There are incredible stories of pronghorn running at speeds of 60 MPH. Regardless of their true maximum speed, they are undoubtedly the fastest land mammal on the continent and sometimes seem to just love speed for speed’s sake.

Antilocaprids were already built for speed for most of their 19-million-year evolution. The earliest known merycodonts had long, slender limbs and were adapted to a running lifestyle. It has been said that the ability to run fast co-evolved with the now-extinct North American cheetah-like cat (Miracinonyx) that had a similar geographic distribution as antilocaprids. This makes complete sense and gives the reader a warm feeling inside to have such a perfect explanation.

This well-worn story of the cheetah and the pronghorn getting fast together is an example of what evolutionary ecologist Stephen J. Gould called a “Just-So Story.” These are made-up stories to describe how a particular trait evolved that are so perfect they must have happened “Just So.”

Gould took this phrase from Rudyard Kipling’s “Just So Stories for Little Children,” where Kipling provided fictional explanations about how animals got their traits. Kipling didn’t intend for readers to think his stories were fact-based. But today, Just-So Stories are used to explain the evolution of animal traits as if they are based on pure science rather than pure speculation.

The cheetah-like cat Miracinonyx does not appear in the fossil record of North America until the end of the Pliocene, when the open savanna was giving way to a more arid monoculture of steppe grasslands about 2.5 million years ago. The fossil beds throughout the West contain abundant evidence of other animals that lived in these grasslands, so the lack of Miracinonyx fossils prior to this time is strong evidence that they weren’t there. Even the true Cheetah (Acinonyx) doesn’t appear anywhere in the world until about 3.5 million years ago. Certainly, there were other predators chasing the great diversity of antilocaprids around, but most were ambush predators.

Further evaluation of Miracinonyx fossils has revealed that it wasn’t really even a cheetah. Analyses of the leg structure, brain shape, and other skeletal features indicates it evolved from the same ancestor as mountain lions, but having characteristics for running fast, which resulted in the early confusion about it being a North American form of cheetah.

Analysis of genetic material extracted from a Miracinonyx specimen from modern-day Wyoming showed it is genetically most closely related to mountain lions and secondarily to the jaguarundi of Mexico and Central America. This analysis of mitochondrial DNA calculates that Miracinonyx and mountain lions split from a common ancestor about 3.2 million years ago.

A lot of writers have made money selling the “Just-So Story” about a North American cheetah chasing pronghorn faster and faster until pronghorn won the race. That may make us feel good to have such a brilliant explanation, but science isn’t built on warm feelings.

Regardless of what made pronghorn so fast, they had what it takes to be the sole survivor of a large, diverse field of competitors. We almost lost them as we were figuring out how to conserve North American wildlife, but we will not risk losing them again. Today, pronghorn have to worry less about predators chasing them and more about human encroachment into their habitat, overuse of the rangelands, blocked movement corridors, harsh winters, drought, energy development, and competition with a multitude of other land uses. It will take our help and vigilance to make sure we are not changing their environment faster than they can evolve or adapt with it.

Read the full article here