The Robbins & Lawrence story began when gunmaker Richard Lawrence arrived in Windsor, Vt. Nicanor Kendall of Kendall & Company recognized the man’s mechanical abilities and hired him straight away at $200 per year. In 1843, Lawrence joined Kendall in the newly formed Kendall & Lawrence Company. The pair leased a modest shop within the confines of Windsor village, and began operating a small gun manufactory.

During the winter the following year, East Coast businessman S.E. Robbins approached the pair with news that the U.S. government was looking to purchase 10,000 rifles for use in the approaching conflict with Mexico. The three men pooled their efforts and established a partnership, put together a bid and sent it to off to nation’s capital. Their successful bid resulted in the U.S. government awarding the new company a contract for the 10,000 Model 1841 “Mississippi” rifles at $10.90 for each unit. This price was ten cents below that of any other bid. A contract was signed on February 18, 1845. The contract called for the guns to be delivered within 36 months.

The nascent gunmaker lacked the land, the manpower, the machinery and the buildings essential to complete this contract, but Lawrence and his colleagues moved rapidly to overcome these obstacles. With only 25 workers on hand, Lawrence saw to the hiring of a large cadre of 150 skilled workers [some researchers put the number as high as 300]. Included within this pool of machinists was Frederick W. Howe, a highly skilled mechanic.

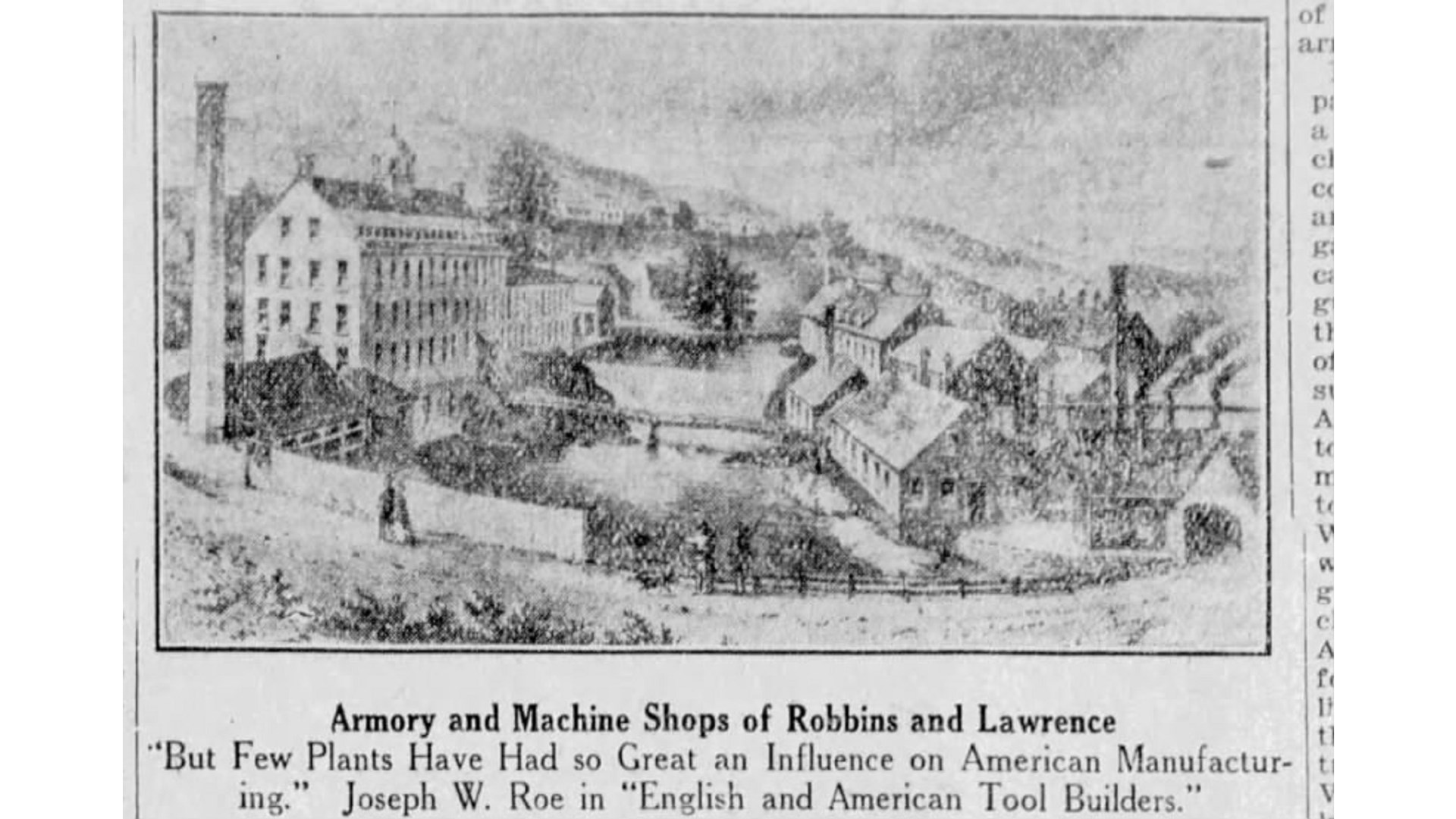

Wasting little time, the three partners purchased land, and in April 1846, laborers began the construction of a three and-a-half story brick armory on the south side of Mill Brook. On the opposite side of the brook, the company’s machine shops were to be built. Most importantly, it was Lawrence who pushed the development of new machine tools to be installed in the factory. Despite having to contend with this workload, the manufacturer completed the contract 18 months earlier than expected and turned a robust profit.

The very first M1841s turned out by the firearms manufacturer were marked “Robbins, Kendall & Lawrence,” but a name change was soon to follow. When Nicanor Kendall left sometime after 1847, the company became Robbins & Lawrence. The locks were now marked Robbins & Lawrence over the U.S. marking, with the date and “WINDSOR” behind the hammer. The barrel flat on the Robbins & Lawrence M1841 was not marked “STEEL,” as were all the Remington and some of the Whitney variants.

Robbin & Lawrence’s success was due to the pioneering use of the relatively new concept of parts interchangeability combined with the effective use of machine tools. Lawrence and Howe provided the talent that cemented the company as a leader in the sphere of machine tools. Lawrence, the original member of the company, added mechanical and business expertise. Frederick Webster Howe was a first-rate machinist, with an innate ability to see what new machine was needed to complete specific tasks.

In the U.S. Census of 1880, Charles H. Fitch penned a piece on interchangeable-parts manufacture that explains and illuminates the workings of a profiling machine that Howe made possibly a bit previous to 1848. The profiling machine illustrated in the article was in use in gun shops throughout the country for several years. Howe, using his machining skills, also devised a barrel drilling and rifling machine. Together, Howe and Lawrence together built a plain miller. This machine was the predecessor of the Lincoln milling machine that would be used by many companies to produce products throughout the late 19th century and even the early 20th century. The gun manufacturing end of the company became a secondary business, while Robbins & Lawrence pursued a trade in the machine tools they had invented. It can be said that the company opened the way for mass production of machine parts, with the launching of the milling machine and the turret lathe into everyday industrial use for production manufacturing.

In 1851, Robbins and Lawrence attained international renown when they participated in the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. The Vermont company exhibited six of its Model 1841 rifles they had produced for the United States Army. Visitors were fascinated by the interchangeable parts that were turned out on machinery created by Robbins & Lawrence. The American gunmakers garnered a medal bestowed by the exhibition. It was this success that opened the door in 1854 for Robbins & Lawrence to secure a contract with the British government, but not for rifles, rather for 150 machine tools needed for a new arms factory. These were delivered to the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock, located near London, for the manufacture of rifles made from wholly interchangeable parts.

Robbins & Lawrence’s M1841 rifles were standardized in their design, fitted with a fixed rear sight, and a .54-cal. bore. But there was no means to attach a bayonet. A number of alterations would come later. A means to fit a bayonet was configured; adjustable sights were added, and the caliber of .54 was changed to a .58 caliber. The Federal government called for these alterations to begin by 1855. On July 4, 1855, the government issued a directive that M1841 rifle bores were to be increased in caliber [to .58], fitted with sword bayonets and long-range rear sights.

The future appeared rosy for Robbins & Lawrence, when in February 1855, Fox, Henderson & Company, a New York concern, was contacted by the English Board of Ordnance to produce 25,000 Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle muskets. Fox, Henderson & Co., in turn, commissioned Robbins & Lawrence to produce the rifles, but the rifle manufacturer assumed the initial order for 25,000 guns was just forerunner of a much larger order, possibly as high as an additional 300,000 rifles, needed to arm the British army during the ongoing Crimean War. Because of this conjecture, Robbins & Lawrence took on a large financial debt to expand its facilities in Windsor. The firearm company also added to this debt by building another gun works in Hartford, Conn. Added to this undertaking was the new machinery and the hired manpower needed for this supposed influx of rifle orders. Robbins & Lawrence needed funds in addition to what it had on hand and turned to a collective of creditors, which included Fox, Henderson & Company.

Commencing in June 1855, the contract with Great Britain called for 650 rifles to be delivered each week. This totaled a delivery of 2,600 guns per month. But various setbacks left the first installment six months late. The manufacture of Robbins & Lawrence Enfields was initially held up because the sample rifles sent to them by the British, for the purpose of fabricating inspection gauges, lacked the proper dimensions. In the end, Robbins & Lawrence was required to fabricate its own gauges, using mechanical sketches, for the purpose of starting rifle production. Matters only worsened from that point on.

At the start of production, deliveries of the Enfields only reached 640 per month, far less that the 2,600 rifles per month that the contract called for. The delivery numbers did eventually improve but still remained below what the contract called for. In March 1856, the Crimean War had concluded, and with that, the British government’s pressing need for rifles ended. In turn, the contract with Robbins & Lawrence was voided.

Following the contract cancellation, Robbins & Lawrence went belly-up in October 1856. Prior the firm’s bankruptcy, it produced around 10,400 Type II P1853 Enfield rifle muskets, but what number were actually delivered to the British remains a mystery. But the Type II P1853 Enfield rifle muskets received by the British were judged 2nd Class, as they were of an outdated pattern (Type II rather than the more up-to-date Type III). These firearms, deemed inferior, were sent to arm British troops in far flung regions of the world.

The Vermont Arms Company, an entity set up by the creditors of Robbins & Lawrence for the purpose of assembling rifles from surplus parts, put together 5,600 rifles from what remained of Robbin’s & Lawrence’s production. Fox, Henderson & Co. accepted these rifles as recompense for their credit interest in the now-defunct company. The Vermont Arms Company followed in Robbins & Lawrence’s footsteps, defaulting in 1858. The Hartford Factory was acquired by the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company, while the Windsor, Vt. property was picked up by two men, E.G. Lamson and Able Goodnow. They formed a company that ultimately manufactured U.S. Model 1861 Special muskets under the company name of Lamson, Goodnow & Yale (LG&Y) throughout the Civil War.

The factories in Hartford, Conn., and Windsor, Vt., were eventually sold at auction, and so followed the idle machinery and leftover rifle parts. The Whitney Arms Company obtained some of those parts and used them in manufacturing its “good and serviceable arms of Enfield pattern.” In perusing period documents, it noted that Whitney acquired enough parts at auction to fashion 4,000 rifles. There is also the possibility that a few of the Robbins & Lawrence Enfields, delivered to Fox, Henderson & Co. earlier, were purchased by Mexican Nationalists to use against Emperor Maximillian I.

“Windsor Enfields” also found their way to the State of South Carolina. The number might have been as high as 710. On Jan. 21, 1861, a shipment from New York City, of rifle muskets to be delivered to Alabama and Georgia, was seized by the New York Police Dept. Twenty-eight cases destined for Alabama were definitely “Robbins & Lawrence Enfields.” The description of the 10 cases intended for Georgia was not as clear-cut, but Civil War texts and images make the case that the Rome Light Guards of Georgia carried at least some “Windsor Enfields” into battle.

So the legacy of Robbins & Lawrence guns lived on in both sides of the Civil War, as well as in far-flung corners of the world where British and native troops may have carried rifles into battle bearing the “Robbins & Lawrence” name, not knowing their substantial contributions to the worlds of armsmaking and mass production.

Read the full article here