Smith & Wesson’s spokesman was at the podium. It was at a swank conference room in Las Vegas on Jan. 17, 1990, and the assembled firearm press was attentive. Rumors had been flying about for several weeks—rumors to the effect that the legendary gunmaker was introducing something really big. Two minutes into Tommy Campbell’s presentation, and rumor became fact. Partnered with Winchester Ammunition, Smith & Wesson introduced a new cartridge and the service pistol to fire it. The pistol was the Model 4006 and the cartridge was the .40 Smith & Wesson. The gun-cartridge combination was calculated to dominate the police service pistol market, with tantalizing possibilities for military application. In those first few frantic months of 1990, that is exactly what happened. That was more than 35 years ago and the beginning of a rather short service life of a cartridge designed to make all handgunners happy.

In the late 1980s, there was a broad concern for those American who were armed in the course of their business—police and other security personnel. The fierce competition for high-capacity 9 mm pistols—sometimes dubbed “The Wondernine Wars”—was resolved when Beretta got the nod for a new military service pistol in 1985. America is a nation of tens of thousands of police departments, all of which control their own armament. Unquestionably, the armament trend was toward 9 mm Luger pistols with greater magazine capacities and several makers were hard at building better 9 mm guns.

S&W introduced its justly famous 3rd Generation pistols in 1988. By that point, there were general rumblings of dissatisfaction with the performance of the 9 mm pistol in police service. It came to a head with the famous FBI Shootout in Miami, where two agents were killed and five wounded in a battle with a pair of bank robbers. The events of that day were studied in depth, and several general principles evolved. Several of the agents were armed with six-shot S&W revolvers, which did not perform well with .38 Special +P ammo and slow reloading. Even the 9 mm semi-automatics used did not really get it done. Things now shifted away from revolvers to semi-automatics that fired lots of more effective cartridges.

It was eerily familiar to another series of events in the 1960s when inadequate performance of police .38 Spl. ammo generated a drive toward a medium revolver. That’s medium in velocity, bore size and bullet weight. We got the .41 Magnum, which clearly delivered all three, but in a big six-shot revolver that was unacceptably heavy for everyone to carry. Actually, there was also a late-1930s spasm of interest in a similar medium bore (0.40″-0.41″ size) revolver over at Colt Firearms. Legendary handgunner J.H. Fitzgerald had made a case for such a concept as early as 1930. Decades later, engineers were working towards the same general thing in a semi-automatic pistol.

With a series of design parameters that seemed mutually exclusive, S&W engineers set to work. First, they sought a sharp increase in on-target performance per shot. Second, they needed an even greater number of shots in the gun. Third, they wanted these things from an easily reloadable semi-automatic that could be handled by anyone and carried by everyone. The gun was actually the easiest part of the equation, as their 9 mm series could be readily adapted.

Smith & Wesson’s “make-it-happen” guys faced some serious challenges when they set about designing a new cartridge. They had an established series of reliable pistols in 9 mm Luger, 10 mm Auto and the venerable .45 ACP. The latter two cartridges were long enough that two columns of either one gave them that all-important capacity. But two columns of .45s or 10 mms created a bulky pistol that was far too much gun for most policemen to handle, much less fire effectively. Such guns could have (and since have) been made, but they’re big brutes—it’s a dimensional problem, not a mechanical one.

S&W could see that and made both .45 and 10 mm single-column guns as compact as they could. The short slide, single-column 10 mm pistol (Model 1076) was adopted by the FBI and (after a bumpy start) proved to be an effective service gun. It was, however, rather large and the ammo developed for service use was distinctly odd. The 10 mm Auto cartridge is roughly 30 percent more powerful than .45 ACP, driving 180-grain bullets to nearly 1,200 f.p.s. This stuff is hot—hard on guns and gunners—with lots of muzzle blast and recoil.

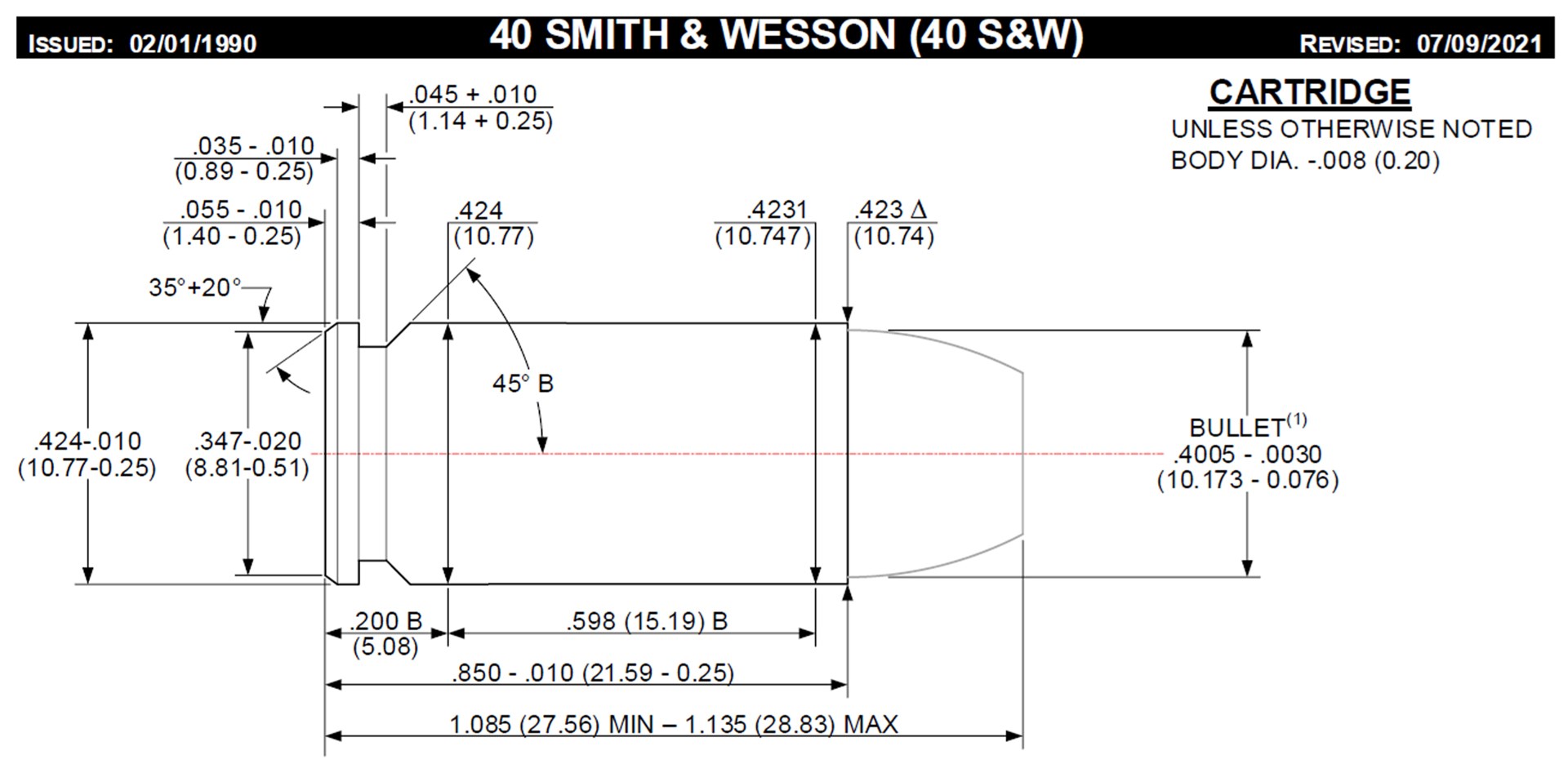

Therefore, the Feds came up with a downloaded 10 mm cartridge that put a 180-grain bullet out the muzzle at 950 f.p.s. This sacrificed around 200-250 f.p.s. off the potential in return for controllability. That’s not efficient, so S&W’s designers followed up on an idea their custom shop had been playing with for some time. It came about in a roundabout way, but they essentially just shortened the 10 mm case to near the 9 mm Luger length, used a 180-grain JHP and achieved velocities of 950 f.p.s. They called it the .40 S&W, and it’s not smoke and mirrors, because they equaled the “FedLite” loading of the 10 mm.

Since the .40 S&W is almost exactly the same length as the 9 mm Luger, the popular double-column 9 mm magazines require only a minor change to the feed lips (sometimes a follower change) to accept .40 S&W cartridges. Their slightly greater diameter meant that you couldn’t get as many .40s as 9 mms, so magazine capacity drops a few. When the cartridge was introduced, it came with little warning. In short order, every maker in the world began frantically modifying their 9 mm service semi-autos to chamber the .40 S&W. It was a resounding success, easily meeting the need for more effective shots, a good quantity of shots and a shootable gun that was no larger than a double-column 9 mm. Most 9mm pistol magazines of that era took 15 to 17 rounds, and their .40 counterparts held 11 to 12.

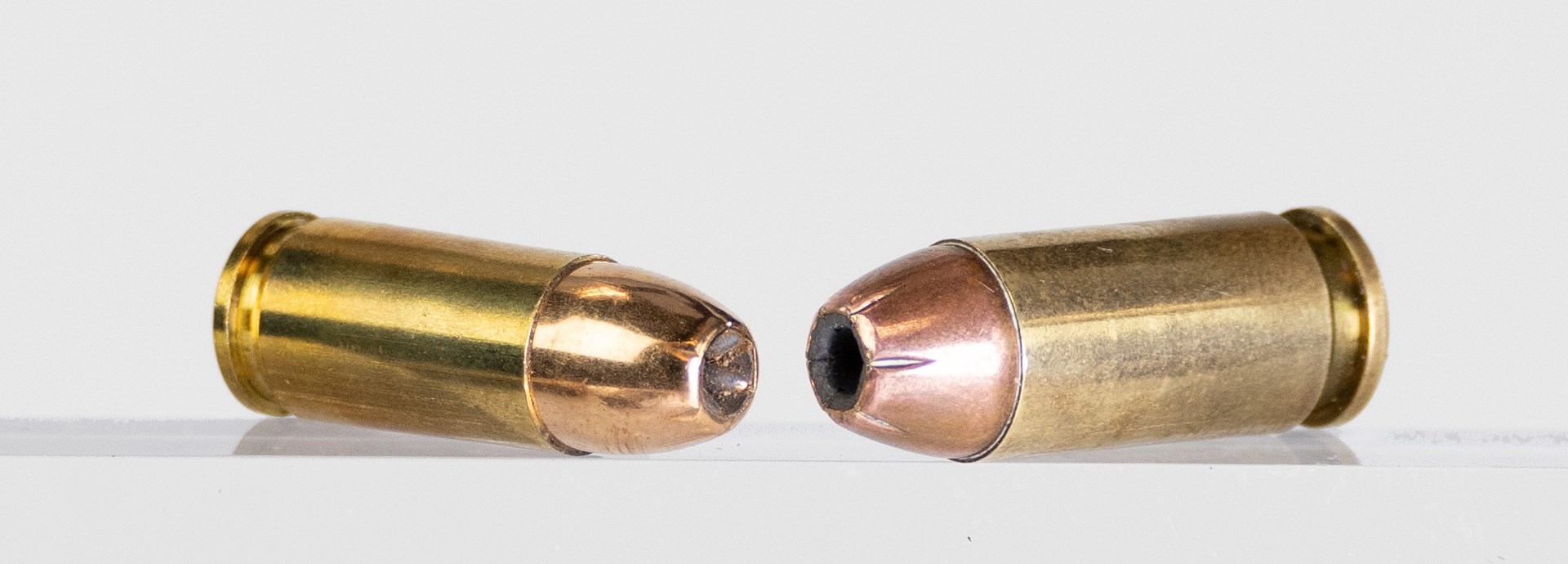

In the first few years of actual service, the .40 S&W ammo and guns did very well. Glock actually got its pistols on the market before S&W, and the remainder of the makers quickly followed suit. Nobody seemed to view the new cartridge as a hunting or match shooting cartridge, although it was accurate enough for either mission. This was a police-service or personal-defense cartridge, designed to halt criminal assaults. In those first few years of the Forty, I watched closely as possible to its effect in police shootings. Obviously, the cartridge was very effective, and there was little complaint about a lack of stopping power. And there was another factor that helped the .40 S&W fix its place in the hierarchy of latter day preferences.

It was the 1994 ban on so-called “assault weapons,” a poorly conceived and written piece of legislation that had several undesirable results for defensive shooters. For this discussion, the most important aspect of that ban included setting a maximum capacity of just 10 rounds for all newly made magazines. That was for any newly produced pistol magazine, no matter what the chambering. Those who clung to the idea of purchasing new 9 mm pistols on the basis of their capacity lost the argument in that they were statutorily limited to 10+1. They could have a 10+1 .40 S&W just as easy as the same size gun in 9 mm. Down-range, on-the- target performance favored the bigger bullet. For tens of thousands of civilian handgunners the 10 unhappy years of the 1994 ban destroyed the capacity argument for 9 mm semi-autos. It also drove the price of second-market, pre-ban, higher-capacity magazines to stupid levels.

But other forces were also at work in this era. Some of it may have been driven by police service (exempt from the capacity ban) wanting much better performing ammo. In an effort to derive better surgical techniques for treating wounds in the military setting, Dr. Martin Fackler developed a credible way to economically simulate them. He ended up using ordnance gelatin, after learning how to produce and calibrate the stuff. Although often unjustly criticized, Fackler literally produced the yardstick by which bullet performance could be measured, and the trend was toward better performance from all ammunition.

As the 1994 ban expired in 2004, the 9 mm Luger cartridge took on a whole new character. It had improved in depth of penetration and degree of expansion, both with greater reliability. Largely, the improvement was in the quality of the hollow-point bullet, but the performance gap between 9 mm and the .40 closed a bit. It was also in this period that slightly heavier 9 mm bullets appeared. When you factor in the post-ban, higher-capacity, 9 mm magazine going back to a normal 13 to 17 rounds (of better ammo), the .40 started losing ground. For quite a while, every time a company developed a new service pistol, they did so in both 9 mm and 40 S&W. But just a few years ago, several of them dropped the .40 from their line. Why?

Nothing changed about the .40 S&W. The improvements in bullet technology developed to improve the 9 mm can also be applied to the .40—with good effect. When both guns were placed before an informed buyer, he was intrigued with the “Forty’s” buck-and-snort, but bought the “Nine” for its expanded magazine capacity. Capacity won.

In the aftermath of such events as the global crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s quite understandable that some people have chosen to arm themselves. Americans who choose to do so are exercising a right guaranteed by the Constitution. Apparently, many have. The arms industry currently sells virtually everything it makes—including .40 S&W guns and ammunition. When this ends—and it will—we will have a new ball game.

Read the full article here