Many volumes have been published telling of the events leading up to the Revolutionary War, as well as the fighting on the first day, April 19, 1775—some more fictitious than true. However, using primary accounts, extant arms, archaeological finds and by studying the battle damage left behind, today we have a much better understanding of what happened, along with the types of firearms that were being used by the men who fought on that pivotal day.

On the night of April 18, 1775, about 750 British regulars began a march from Boston, Mass., to Concord, a town about 18 miles to the west, to destroy warlike stores being hidden there. They had been purchased by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress’ Committee of Safety and Supplies to form and supply a provincial army once the inevitable war broke out. Colonel James Barrett of Concord oversaw the supplies, and the lists of these stores still survive. From artillery, cannon shot, tents, musket balls, powder, cartridges and provisions to medical kits, wooden bowls, spoons and 15,000 canteens, it is very evident why the British felt they should go to Concord and destroy this materiel.

The British regulars were ferried from Boston Common to Phipps Farm, a piece of land on the Cambridge side of the Charles River, owned by loyalist Richard Lechmere. Once assembled, they begin their march to Concord. In a letter to an unknown friend, Lechmere wrote, “At about 11 oClock at night 700 grenadiers and light Infantry were carried in Boats to my farm, and order’d to march to Concord in order to Destroy some magazines of stores that the Rebels had Lodg’d there, but according to Custom by some means or other they obtained such early intelligence of the design.”

A little earlier that night, at about 7 or 8 p.m., a British patrol had been spotted on the Concord Road in Cambridge and word got out that the regulars were on the move. Elbridge Gerry, a member of the Committee of Safety and Supplies, had stayed the night at the Black Horse Tavern in the Cambridge village of Menotomy on April 18th after a meeting of the committee. He wrote a note to John Hancock, who was staying just up the road in Lexington with Reverend Jonas Clarke, that he had seen the British patrol heading west. Reverend Clarke mentioned the information reaching Lexington:

“On the evening of the eighteenth of April, 1775 we received two messages; the first verbal, the other by express, in writing, from the committee of safety, who were then sitting in the westerly part of Cambridge, directed to the Honorable John Hancock, Esq; (who, with the Honorable Samuel Adams, Esq; was then providentially with us) informing, that eight or nine officers of the king’s troops were seen, just before night, passing the road towards Lexington, in a musing, contemplative posture; and it was suspected they were out upon some evil design.”

After receiving the written message, Hancock wrote back to Gerry at 9 p.m.: “I am much oblig’d for your Notice, it is said the officers are gone Concord Road, & I will send word thither I am full with you we ought to be serious, & I hope your decisions will be effectual.” A few hours later, Paul Revere and William Dawes, along with many other riders unknown to history, would sound the alarm throughout the countryside. Local militia and minute companies quickly awoke to take up their arms, form and march toward the town of Concord.

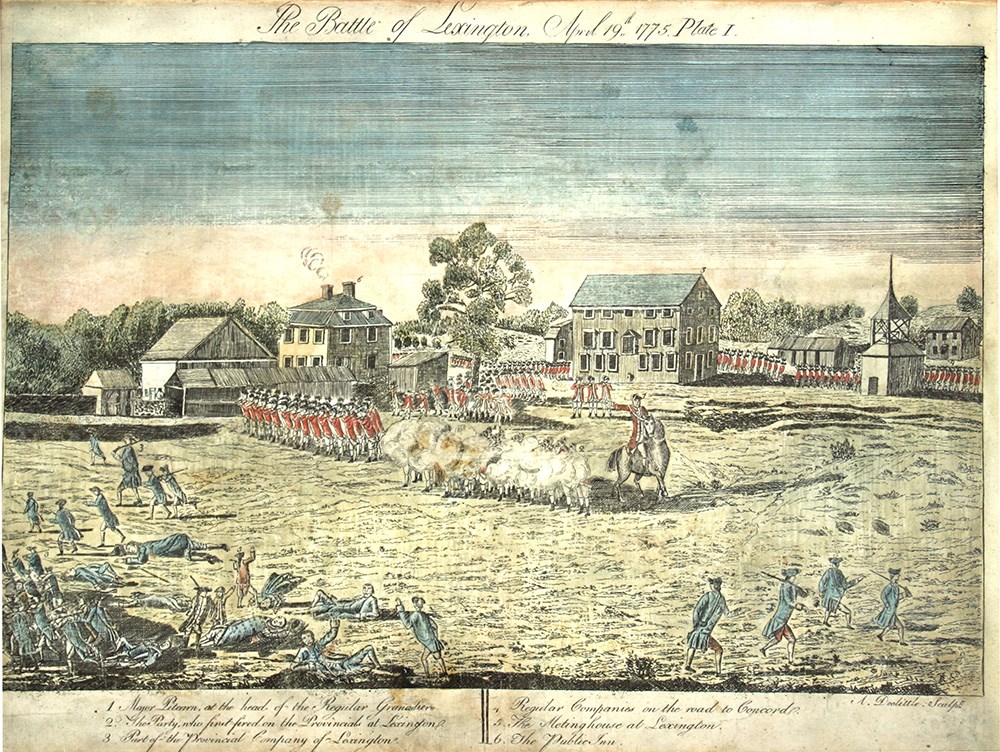

At dawn on April 19th, the British column marched through Lexington on its way to Concord. Captain John Parker, commander of the Lexington militia, stood with his company on the green awaiting their arrival. Just days later, in his deposition of the events, John Robbins, a member of Parker’s company, wrote about what happened next:

“Being drawn up sometime before sunrise, on the green or common, and I being in the front rank, there suddenly appeared a number of the King’s troops, about a thousand, as I thought, at the distance of about sixty or seventy yards from us, huzzaing, and on a quick pace towards us, with three officers in their front on horse back, and on full gallop towards us, the foremost of which cried, throw down your arms, ye villains, ye rebels, upon which said company dispersing, the foremost of the three officers ordered their men saying fire, by God, fire, at which moment we received a very heavy and close fire from them, at which instant, being wounded, I fell, and several of our men were shot dead.”

Robbins was badly wounded, shot in the back of the neck with a .69-cal. ball that traveled through his neck, shattering his lower jaw and exiting his mouth. Nine others were wounded and eight killed. After the smoke had cleared, the column reformed, cheered and marched off to Concord.

As the British left Lexington, there was a straggler who was captured by Joshua Simonds, one of Capt. Parker’s men. His story was passed down and states that the British prisoner, “… was an Irishman, fully six feet in height, and manifested but little interest in the morning excursion. To my inquiry as to his delay, I found he had been overcome with liquor, lingered behind, and lost his companions. I took him to a place of safe keeping, away from the possible line of march of the army when they should return. He was thus the first prisoner captured on that day.”

Simonds’ story continues: “His musket, a good specimen of the king’s arms, I also took, appropriated to my own use, and at the close of that day turned it over to Captain Parker as public property. I was not able to ascertain the remainder of the man’s experience, but the gun is of interest to all.”

In 1860, the captured British musket was donated by Parker’s grandson, Theodore Parker, to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The gun is a British Pattern 1756 Long Land musket and is marked on the barrel to the 43rd Regiment of Foot. Given that it is a Long Land, and that the captured man was “fully six feet in height,” it was more than likely captured from a grenadier of the 43rd. A petition in the Massachusetts State Archives written by British prisoners held in Concord lists a Duncan McDonald. He was the only 43rd grenadier captured on April 19th and may have been the soldier who “had been overcome with liquor” and surrendered his musket to Simonds.

Concord had received the alarm prior to the arrival of the regulars and began removing or hiding as much of the warlike materiel as they could in a short amount of time, as well as assembling the minute and militia companies. Thaddeus Blood, a member of Capt. Nathan Barrett’s militia company, remembered, “On the 19th of April 1775, about 2 o’clock in the morning I was called out of bed by John Barritt a Sergt of the Malitia Comy to which I belonged. (I was 20 years of age the 28th of May next following). I joined the company under Capt. Nathan Barrett (afterward Col.) at the old court house about 3 ’oclock and was orderd to go into the court house to draw amunition, after the company had all their amun we were paraded near the meeting house.”

According to Blood, the Concord men were soon joined by others from Lincoln, and it was decided that they should march toward Lexington: “We were then formed, the minute on the right, & Capt. Barrett’s on the left, & marched in order to the end of Meriam’s hill then so called. & saw the British troops a coming down Brook’s hill. The sun was arising & shined on their arms & they made a noble apperance in their red coats & glising arms—we retreated in order, over the top of the hill to the liberty pole erected on the heighth opposite the meeting house & made a halt, the main body of the British marched up in the road. & a detachment followed us over the hill & halted in half gun shot of us, at the pole we then marched over the Burying ground to the road, and then over the Bridge to Flint’s Hill, or punckataisett, so called at that time, & were follow by two companies of the British over the Bridge.”

After their arrival in Concord, the regulars searched the town and destroyed some of the warlike stores, although much of the materiel had been hidden or moved prior to their arrival. Some gun carriages and wheels were burned on the common, the trunnions were knocked off three 24-lb. cannons, musket balls were tossed into the Milldam, and flour, salt fish and other supplies were destroyed.

Concord minuteman Amos Barrett remembered, “Thair was in the town House a number of intrechen tools witch they carried out and Burnt them. At last they said it was better to Burn them in the house and sot fire to them in the house, but our people Begd of them not to Burn the house, and put it out. It wont long before it was set fire again but finaly it warnt Burnt. Their was about 100 Barrels of flower in Mr. Hubbards malt house, the Rold that out an nockd them to pieces and Rold some in the mill pond, whitch was saved after they was goon.”

At around 9 a.m., the provincials, numbering around 450, were stationed on a rise above the North Bridge. Smoke from the burning stores alarmed the men, and it was decided to march to the bridge and into town. One of the British light infantry companies was at the bridge, while two companies were on the west side of the bridge.

With the provincials marching toward them, Blood remembered, “They then retreated over the Bridge & retreating took up 3 plank, and formed part in the road & part on each side, our men the same time marching in very good order, along the road in double file. At that time an officer rode up & a gun was fired. I saw where the Ball threw up the water about the middle of the river, then a second & a third shot, & the cry of fire, fire was made from front to rear. The fire was almost simultaneous with the cry, & I think it was not more than 2 minutes if so much till the British run & the fire ceased.” Two provincials were killed, as were two British soldiers, with another mortally wounded. British light infantry then retreated back to Concord center.

Captain David Brown of Concord commanded one of Concord’s two minute companies during the North Bridge fight and lived just on the west side within view of the bridge. His musket survives, which is built from a variety of parts. It has a bore of .75 caliber, a locally made iron ramrod, some imported or re-used fittings, and it had a lug on the underside of the barrel near the muzzle to attach a bayonet.

A recent archaeological study conducted on the east side of the North Bridge found five fired provincial overshot in numerous different calibers, from a .41-cal. swan shot to a .70-cal. ball, which covers a variety of the ammunition types fired from arms used by the colonists that day.

For another two hours, the British searched for stores, then formed to march back. They were attacked a mile outside of town by provincial forces. Thus began the “running battle” as they attempted to get back to Boston. After the devastation in Lexington earlier in the morning, Capt. Parker had reformed his company to march off and meet the regulars upon their return. On a piece of ground on the Lexington/Lincoln line, his men waited. As the British column passed by, Parker’s men fired and retreated to hit them again further down the road. Archaeological digs conducted in that area have found the spot where the action took place. Musket balls fired by the regulars have been found, as was a row of fired balls from provincial fowling pieces, which were being used by many of the Lexington men for their militia service.

Another gun donated in 1860 by Theodore Parker to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts was the fowling piece carried by his grandfather, Capt. John Parker. It is a no-frills gun with a .64-cal. bore and is of typical New England form with a dropped French-style butt. The barrel was shortened sometime in the 19th century before its donation to the Commonwealth.

At the Ebenezer Fiske house in Lexington, James Hayward of Acton stopped at a well to get a much-needed drink of water. He saw a British soldier who had been looting the house come out the front door, and they both fired at each other. The British soldier fell dead and Hayward was mortally wounded—he didn’t survive for long.

Rebekah Fiske, daughter-in-law of the owner of the house, wrote, “After the rattle of musketry had grown somewhat weaker from distance, and my heart became more relieved of its apprehensions, I resolved to return home. But what an altered scene began to present itself, as I approached the house—garden walls thrown down—my flowers trampled upon—earth and herbage covered with the marks of hurried footsteps. The house had been broken open, and on the doorstep—awful spectacle—there lay a British soldier dead, on his face, though yet warm, in his blood, which was still trickling from a bullet-hole though his vitals. His bosom and his pockets were stuffed with my effects, which he had been pillaging, having broken into the house through a window. On entering my front room, I was horror-struck. Three mangled soldiers lay groaning on the floor and weltering in their blood, which had gathered in large puddles about them.

“‘Beat out my brains, I beg of you,’ cried one of them, a young Briton, who was dreadfully pierced with bullets, through almost every part of his body, ‘and relieve me from this agony.’ You will die soon enough, said I, with a revengeful pique. A grim Irishman, shot through the jaws, lay beside him, who mingled his groans of desperation with curses on the villain who had so horridly wounded him. The third was a young American, employing his dying breath in prayer. A bullet had passed through his body, taking off in its course the lower part of his powder-horn. The name of this youthful patriot was J. Haywood [Hayward], of Acton. His father came and carried his body home; it now lies in Acton graveyard.”

As mentioned, Hayward was shot through his powder horn, with the ball leaving a round hole where it entered and blowing out the opposite side sending not only the .69-cal. ball, but also shards of horn and fragments of clothing, into his horrific wound. The horn was preserved by his family before being donated to the town of Acton.

As the British regulars made it back to Lexington center, they met about 1,000 reinforcements with two 6-lb. field pieces, which had been sent out of Boston to meet the retreating column. Reverend William Gordon stated in his history, “But a little on this side Lexington Meeting-House where they were met by the Brigade, with, cannon, under Lord Percy, the scene changed.” After the arrival of Lord Percy, the fighting became more intense and vicious, and, as mentioned by Reverend Gordon, homes were looted and put to the torch. Other houses became shooting positions for provincial minutemen and militiamen, as well as the place where many would meet their demise.

There are many accounts that survive written by both sides relating to what happened that day, and one of the most detailed was penned by an unknown British officer who commanded a company of the 4th Regiment of Foot as a part of Lord Percy’s relief brigade. He wrote, “Such a scene of Confusion never was & I saw several men killed by our own people firing on them from eagerness you would see a Party of Soldiers firing at the front of a House & another on its rear whilst the main body were pelting away at the upper windows by which means many of our own people fell even after they were in the House, & all the World could not prevent it, one Soldier of ours got 11 Balls in him by that means, 4 of which have been cut out, & he is still alive.”

In the Cambridge village of Menotomy, some of the heaviest fighting of the day took place. One of those wounded was Nathan Putnam of Danvers. He was struck in his right shoulder by a British musket ball and lost his musket. Seen in newspapers soon after the battle was an advertisement looking for his gun, “Lost in the battle of Menotomy by Nathan Putnam of Captain Hutchinson’s Company who was then badly wounded a French firelock marked D No 6 with a marking iron on the breech Said Putnam carried it to a cross road near a mill Whoever has said gun in possession is desired to return it to Colonel Mansfield of Lynn or to the selectmen of Danvers and they shall be rewarded for their trouble.” His musket was more than likely an older Model 1728 French Infantry musket, many of which were captured during the Seven Years War and sold commercially in Boston.

Across the street from where Putnam was wounded is the Jason Russell house. It is owned today by the Arlington Historical Society and kept as a museum. There were at least 12 provincial soldiers killed in and around the house, and it is not known how many regulars died there. The unknown officer of the 4th Regiment of Foot mentioned above was there and stated, “In one of those Sallys I had a very narrow escape having a Granadier of the 5th, a soldier of ours, & a marine killed all around me, but we soon got into the house & I counted 11 Yankies dead in it & the orchard, one villain had 73 Balls in his Bag & 2 horns of Powder.” The fighting continued until the regulars made it to Charlestown and the relative safety of the Bunker/Breed’s Hill area, which a few months later would be the scene of more heavy fighting.

On the morning of April 20th, Reverend David McClure rode out to the scene of the battle. He wrote in his diary, “Determining to see what had been done on the rout of the enemy, I rode to Watertown & from thence came on the road to Lexington. I went almost to the meeting house, were the first American blood was wantonly spilt, but the rain necessitated me to return. Dreadful were the vestiges of war on the road. I saw several dead bodies, principally British, on & near the road. They were all naked, having been stripped, principally, by their own soldiers. They lay on their faces. Several were killed who stopped to plunder & were suddenly surprised by our people pressing upon their rear. The houses on the road of the march of the British, were all perforated with balls, & the windows broken. Horses, cattle & swine lay dead around. Such were the dreadful trophies of war, for about 20 miles!”

By the end of the day on April 19, there were approximately 5,000 militia and minutemen who had followed the British back to the relative safety of Boston. Some were too late to enter the fight, but were ready to lay siege on the town of Boston. Within a few days there would be more than 20,000 men, not just from Massachusetts, but also from the surrounding colonies. It would be almost a year before British forces would evacuate Boston and another seven before the bloody war would come to an end with the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

The accounts written by participants, as well as the surviving arms, battle damage and archaeological evidence, not only bring the events closer to us but are a tangible reminder of the men who gave their lives or risked everything to take up arms and participate in the birth of the United States of America.

Read the full article here