It is a military conundrum for the ages. The infantry demands more firepower and receives the death-dealing engine known as the machine gun. Shortly after the first bursts are fired, the tired infantrymen exclaim, “This gun is too heavy!” and work proceeds to create a lighter, easily portable variant. When the new, lighter firearm reaches the troops, they cry, “There is not enough magazine capacity, and the air-cooled barrel overheats too fast!” Firearm designers and commanding officers are frustrated. Meanwhile, the long-suffering infantry bemoan “… and the gun is still too heavy!”

This is a tale that is true for many machine guns. In the latter stages of World War I, and in the years immediately after the conflict, the initial attempts to create a true “light machine gun” (LMG) were fraught with weighty complications and uncomfortable comprises. One of these early LMGs, now often overlooked or forgotten, is the Finnish M/26, devised from the fertile mind of notable firearm designer Aimo Lahti and a young technical expert named A.E. Saloranta. Lahti handled the design, and Saloranta took care of the administrative and political details.

Tiny Finland had a great need for machine guns when the first prototype of the M/26 was made in the summer of 1925. The new nation had transitioned from a grand duchy of Czarist Russia, and then successfully defended against a communist takeover during the civil war of early 1918. With assistance from Germany, the Bolsheviks were driven out of Finland. The Finnish Civil War had been fought with a hodgepodge of infantry arms, mostly of Russian origin. Heavy machine guns consisted of the ubiquitous water-cooled Maxim (7.62×54 mm R), and the M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun, which was popular in several calibers in Eastern Europe. Light machine guns included the Madsen LMG (many in 7.62×54 mm R) and the Lewis Gun (some chambered in 7.62×54 mm R).

By 1925, the Finns saw the Soviet Union become increasingly aggressive, and tests were sped up to select a new light machine gun to standardize in the Finnish army. The M/26 was chosen in the design competition over other solid candidates, including 7.62×54 mm R versions of the Vickers-Berthier (24.4 lbs., magazine fed), the Hotchkiss M1922 (21.1 lbs., magazine or strip fed), and the M1922 Browning Automatic Rifle (24 lbs., magazine fed). Despite the urgency to get the new light machine gun designed, the M/26 fell victim to “hurry-up-and-wait” production delays and was not available for service until 1930.

The selective-fire M/26 uses a short-recoil action and fires from an open bolt. The cyclic rate is about 600 rounds per minute. There is a flimsy bipod that folds underneath the barrel, attached by a spring-loaded clip. The quality and strength of the bipod certainly doesn’t match the robust construction of the gun. The sights are a U-notch type and are adjustable up to 1,500 meters. By most accounts, the M/26 is quite accurate, with manageable recoil. If fired from the shoulder or from the hip on full automatic, the muzzle climb is described as “severe.”

The M/26 is well-machined with very close tolerances—and it seems like this was the beginning of its problems. The complex recoil assembly was mounted in the buttstock, and since it doesn’t handle the introduction of dirt or moisture well, frontline troops were forbidden to disassemble that portion of the gun. Sadly, when M/26 was initially issued to troops at the beginning of the Winter War, the guns were covered in grease. Finnish troops followed instructions and did not touch the rear-mounted recoil assembly, which, of course, was also covered in grease and froze solidly in the frigid arctic environment. This began an unfortunate series of events that led to the M/26 being labeled the “accumulated malfunctions Model 26,” and there was a general distrust of the firearm until the troops received more training.

A Low-Capacity Magazine

Much like the Browning Automatic Rifle, the M/20’s 20-round magazine was one of the gun’s biggest problems that was never resolved. The double-stack, single-feed design is particularly robust, and its springs are very strong. So strong, in fact, that it is virtually impossible to load more than a handful of rounds into the M/26 magazine without using one of the magazine’s loading tools. Apparently, Finnish troops would also short-load the magazines by several rounds to prevent jams, which further diminished the already-small magazine capacity.

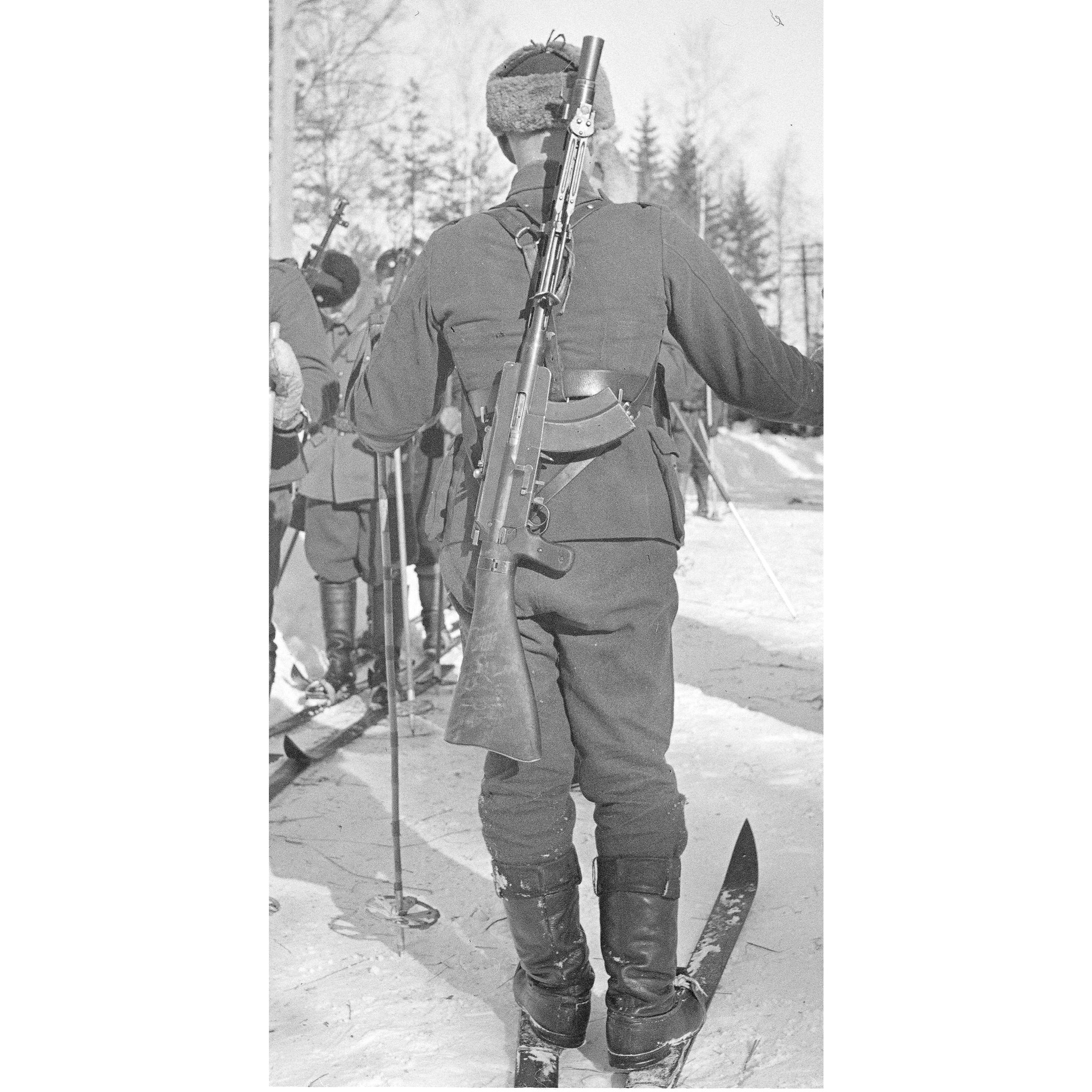

Interestingly, the Finnish army in the Winter War called for 90 M/26 magazines to be carried into combat alongside the gun. The gunner and his assistant were detailed to carry 10 magazines each, and this required the rest of the squad to carry the remaining 70 magazines in groups of 10 in large canvas bags. This “squad-supports-the-MG” style would be seen again in World War II when German infantrymen were burdened with spare ammo belts (and barrels) for their unit’s MG34 and MG42 machine guns. For the Finns in the Winter War, this large load of magazines shows just how difficult and time-consuming they were to load. Hand-loading in combat was highly unlikely.

There were a few experiments to provide a 75-round “pan” magazine for the M/26, most notably in the M/26-31 variant. These higher-capacity magazines were originally intended for aircraft use and were never issued to the infantry.

An Eye Towards International Sales

The Finns had predicted that England and Germany would go to war again before too long, and so they developed the M/26 variants in .303 British and 8 mm Mauser to sell to the prospective opponents. Interest never materialized with those nations, and by 1933, the Finns were offering the M/26 for sale on the international market. The LMG was interesting to many, but the price tag was far too high for most.

One significant order (for 30,000 guns) came from China. The Chinese were fighting a Japanese invasion and placed an order for 30,000 of the M/26-32 chambered in 8 mm Mauser. After a little more than 1,000 M/26s had arrived in China, the Japanese government raised such a stink in the League of Nations and other political channels that the Finns succumbed to international pressure and terminated the deal.

Some promotional material from 1933 for the M/26 provides some interesting insight as to how the LMG was positioned as a general-purpose machine gun with cost-effective features to ease the sticker shock over the price:

“The greatest advantage of this machine gun is that it at last solves the problem of a universal machine gun of different calibers. It is designed so that after fitting in different operational parts, the firing of cartridges of different calibers is possible. At present, machine guns with firing mechanisms for British and German army cartridges are being made. During the manufacture, trials have also been made with 7.9mm and 6.5mm military cartridges and it was proven then the functioning and accuracy of the weapon were equally good as with the above-mentioned ammunition. It is accordingly fully possible to chamber the weapon for every known cartridge powerful enough to operate its mechanism.”

The Finns also noted this odd, but seemingly sensible, feature of the M/26:

“… In a state of war, in case of capture of any of the above kinds of cartridges, this machine gun can use the ammunition by putting in other operating parts in the receiver. These changes can be made during the actual fighting, and they would only take some eight seconds to perform, provided the necessary operating parts are brought along by the machine gun section. Every state, however, knows their possible future opponent in war, and what kind of ammunition they will use and can always keep a certain number of exchange systems in stock.”

A Russian Replacement

Throughout the Winter War (Nov. 30, 1939 to March 13, 1940) the Finns encountered large numbers of the Soviet Degtyarov light machine gun, the DP-27/DP-28. In the course of inflicting horrific casualties on the Red Army (more than 160,000 killed or missing in less than four months), the Finns also captured nearly 6,000 Soviet troops. They also picked up a large number of DP-27 LMGs. Chambered in 7.62×54 mm R, the 25-lb. DP-27 was gas-operated and fed by a 47-round pan magazine. The Soviet LMG was simple, rugged and effective—or at least effective enough. What it lacked in sophistication and production quality, it made up for in serviceability in the frost-bitten combat zone. Plus, the Finnish army couldn’t beat the price. Nicknamed “Emma” by the troops, it quickly, albeit unofficially, replaced the M/26 in Finnish service.

Production of the M/26 ended in 1942, with fewer than 5,000 examples made. By the end of the Finn-Soviet Continuation War (June 25, 1941 to Sept. 19, 1944) there were more than 9,000 captured Soviet DP-27s in Finnish service, compared to only about 3,000 M/26s.

The M/26 Historical Perspective

As perception equals reality, the M/26 has often been viewed as a failure. But pushing past the surface level of negative descriptions provides a better understanding of Lahti’s LMG design in proper historical context.

Looking at the international roster of light machine guns in 1925 reveals just a few choices:

That is the consideration set at the time—and thus Lahti’s M/26 design compares favorably as a light machine gun within the parameters of the available options of the era. Just a few years later, the light machine gun category would change dramatically, as new light machine guns like the Soviet Degtyarov, the Czech ZB vz.26 and the German MG34 would significantly influence firearm design for the coming Second World War.

Read the full article here