Since at least the dawn of the 20th century, Marines have been known for their marksmanship skills both on the shooting range and on the battlefield. Although Marines had manned the “Fighting Tops” of the sailing navy and swept the decks of enemy ships with smoothbore musket fire, the emphasis on shooting ability did not become a distinct Marine tradition until they were issued accurate magazine-fed repeating rifles. Some of those, like the Model 1903 Springfield, soon gained a cult status among Marines. Every Marine, regardless of rank or military occupational specialty, must qualify with the issue service rifle on a regular basis, and the ability to have all hands on the firing line in a tight situation has paid dividends for the Corps on more than a few occasions during the past 100-plus years.

According to the lore of the Corps, the Continental Marines were first recruited at Philadelphia’s Tun Tavern, in response to a local newspaper advertisement in 1775 for “A Few Good Men.” The Continental Marines had been authorized by the Continental Congress on Nov. 10, 1775, which is exactly 250 years ago this month. After sterling service afloat and on land during the American Revolution, the Continental Marines were disbanded in 1783, but the unit was soon re-established in 1798 as the United States Marine Corps during the “Quasi-War” with Revolutionary France. Marines were now armed with locally made, brass-mounted, “Marine” .69-cal. flintlock muskets. Apart from some small shipboard actions, the next test of the Marine Corps was the suppression of the Barbary Pirates on the “Shores of Tripoli,” the Mediterranean coast of North Africa, where a handful of Marines under a single lieutenant successfully led a ragtag mercenary force in seizing the city of Derna in 1805.

The Marine Corps was deeply involved, again at sea and on land, during America’s “Second War of Independence” with Britain—the War of 1812. Afterward, Marines found themselves fighting Native American tribes during the period of “Manifest Destiny” (America’s expansion westward and southward in North America), and in another bit of Marine Corps lore, then-Commandant, Brig. Gen. Archibald Henderson took a battalion of Marines to Georgia and Florida in the 1830s after nailing a note to the closed gate of the Washington, D.C., Marine barracks stating, “Gone to fight the Indians. Be back when the war is over.” Although the Corps had briefly considered the new Model 1819 Hall breechloading rifle, Marines were carrying brass-mounted flintlock British Brown Bess muskets into the 1830s, as these arms did not rust as badly as iron-mounted, Springfield-type muskets while aboard ship. While fighting the Seminole Indians in Florida, Marines experimented with the latest in percussion arms and with Colt revolving carbines. Marines also fought the newly founded Mexican Republic in California and in Mexico, and the assault on the Mexican citadel of Chapultepec added another phrase to the “Marines’ Hymn”—“From the Halls of Montezuma”—with the Marines now armed with variants of the Model 1816 Springfield .69-cal. flintlock musket. These muskets served Marines well in small actions around the globe in the 1840s and 1850s, as American sea power and influence spread to Asia and the Pacific basin.

The primary duty of Marines during ship-to-ship battles in the days of sailing ships was to man the “Fighting Tops” and sweep the upper decks of enemy ships with musket fire. Until the advent of accurate, magazine-fed, bolt-action rifles, however, individual marksmanship skills were not pursued vigorously since their smoothbore muskets were made without rear sights. Seen here is the National Museum of the Marine Corps’ “Fighting Tops” exhibit. Courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps

Sadly, like the other services and much of the civilian population, Marines found themselves on opposing sides during the Civil War. Almost one-third of the existing officer’s corps followed their respective states into secession, most of them joining the Confederate States Marine Corps. As they had done in the past, Marines on both sides fought bravely in actions at sea and on land, conducting numerous amphibious raids and landings on southern coasts and rivers. While the U.S. Marine Corps entered the war with converted .69-cal. flintlock muskets, as well as newly made .69-cal. smoothbore and rifled percussion muskets, .58-cal. M1861 (and later M1863) Springfield rifle-muskets became standard-issue for U.S. Marines during the Civil War. Tin-plated Spencer M1860 Navy rifles chambered for .56-52 were also issued to some small shipboard detachments. Meanwhile, the Confederate Marines carried .577-cal. Enfield rifles of varying types, imported from England. After the conclusion of the South’s unsuccessful bid for independence, Marines were still carrying “Muzzle-Fuzzles” (as one Marine officer referred to his men’s Springfield rifle-muskets) and used them in Korea during an intervention there in 1870.

When modern magazine-fed repeating rifles, using smokeless powder and jacketed bullets, were issued to Marines, their shooting skills improved markedly, and the Corps embraced an intensified marksmanship program. The revolutionary 6 mm M1895 Winchester-Lee “straight pull” rifle was even featured on the Marine Corps’ new (1896) Enlisted Good Conduct Medal—the example shown here was awarded to Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller. Rifle courtesy of the National Firearms Museum. Medal courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps

In the latter years of the 19th century, the U.S. Navy was transitioning its ships from sail to steam, and its rifles from single-shot breechloaders to magazine-fed repeaters. However, the Marine Corps clung to the Army’s “Trapdoor” .45-cal. single-shot rifle until the advent of the revolutionary 6 mm M1895 Lee-Navy straight-pull rifle. With this new rifle, the Marine Corps began to upgrade its marksmanship program and hone its marksmanship skills. It would not be until the early years of the 20th century, however, that a serious attempt to start winning interservice shooting matches was undertaken. The “Trapdoor” Springfield and the Lee-Navy rifle served Marines abroad well in numerous small expeditions all over the globe, as did new .38-cal. Colt revolvers for the officers and select non-commissioned officers. While some Marines had been manning “great guns” on sailing ships since the early 19th century, and Marines had trained with boat howitzers and naval landing guns since the 1850s, they were now also operating Gatling guns and Hotchkiss revolving cannons aboard ship in the new “steel navy.”

By the mid-19th century, rifled muskets were being issued to Marines, and the potential for accurate fire against an enemy on shore increased—as demonstrated in the “Cpl. Mackie at Drewry’s Bluff” exhibit at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, based on a painting by Col. Charles H. Waterhouse, USMCR, of the same title. Courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps

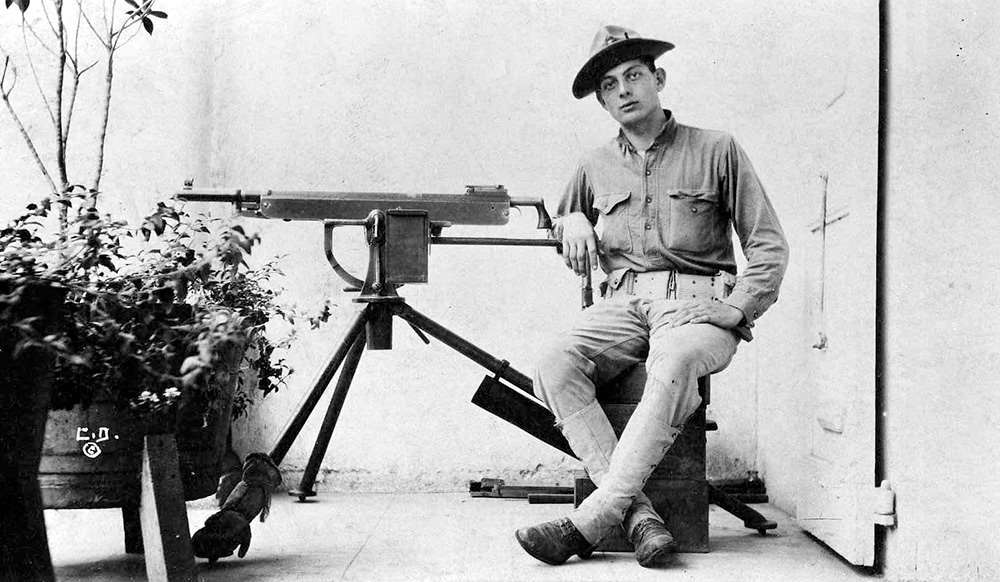

After receiving mixed reviews during the Spanish-American War, the M1895 Lee-Navy rifle was replaced by the Army’s .30-40 Krag-Jorgensen, and both rifles were used by Marines during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 in China. Then-Pvt. Dan Daly was awarded his first Medal of Honor for single-handedly defending his post on the wall in Peking with his Lee rifle. The phrase “Civilize ’em with a Krag” was included in a popular song during the Philippine Insurrection at the turn of the 20th century, and Marines had now added the M1895 Colt “Potato Digger” machine gun (so named for its forward operating arm that plowed up the earth when used on a low ground mount), first in 6 mm and later in .30 caliber, to its inventory of arms.

In addition to its wheeled mount, the Colt M1895 “Potato Digger” could be mounted on a tripod while in Marine service. National Museum of the Marine Corps photo

As a result of the Marines’ experience at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, during the Spanish-American War, the Corps found a new purpose in the modern steel navy. No longer needed to man the “fighting tops” of sailing ships, Marines continued to serve as guards and landing parties aboard ship, but now new units were organized to seize and defend coaling stations for the coal-burning U.S. fleet around the globe. These Advanced Base Force units were now tasked with manning heavy seacoast artillery and anti-aircraft guns—since aviation was becoming a part of the world’s military scene. Indeed, the Marine Corps’ first involvement with aircraft was in 1912, just about the time that the Marine Corps re-armed with a new service rifle and pistol.

The .30-cal. M1903 Springfield rifle gradually replaced the .30 Army “Krag” rifles in the Corps over a period of four or five years, and Marines quickly became expert in its use. With a rear sight made for precise long-distance shooting, and a smooth bolt-action, the “Oh Three” was a marksman’s delight. Moreover, the Marine Corps had replaced its Colt revolvers—the M1905 in .38 Colt and the M1909 in .45 Long Colt—with the revolutionary Colt Model 1911 .45 ACP semi-automatic pistol in 1912. Both the Springfield rifle and the Colt pistol were to play major roles in Marine Corps history in the following decades. The heavy M1895 Colt machine gun, often mounted on a wheeled handcart, was being replaced by the light .30-cal. M1909 Benêt-Mercie Hotchkiss “machine rifle” by the outbreak of the “Banana Wars.”

The Banana Wars of Central America and the Caribbean occupied much of the Marine Corps’ attention and resources before, during and after World War I. America’s entry into World War I in 1917 found the Marine Corps stretched out in detachments and on ships around the globe, and it expanded nearly six-fold during the war. The Corps’ leadership was experimenting with armored scout cars, troop-carrying trucks, automobiles and motorcycles, as well as upgrading its machine guns. The Navy had adopted the dependable American-designed .30-’06 Sprg. Lewis light machine gun in 1916, and Marines then took it with them to France.

The U.S. Marine Corps always has been, and still is, America’s expeditionary “Force in Readiness,” responding wherever and whenever needed. The “Banana Wars” of the early 20th century involved Marines safeguarding American lives and interests across the Caribbean and Central America while using their .30-cal. M1903 Springfield rifles and .45-cal. M1911 pistols, as seen here during the 1915 Haitian Campaign. “Smedley Butler At Fort Riviere” by Col. Donna J. Neary, USMCR

With a desire to have the Marine Corps heavily involved in Europe, the commandant organized a brigade of Marines, and, under the slogan “First to Fight,” sent its lead elements to France within a few months of America’s declaration of war on Germany. This Marine brigade formed the 4th Infantry Brigade of the Army’s 2nd (Regular) Division and covered itself in glory. With its Lewis machine guns replaced by French heavy Hotchkiss machine guns and Chauchat automatic rifles in 8 mm Lebel, the 4th Brigade (two infantry regiments and a machine gun battalion) fought through the battles of Belleau Wood, Soissons, St. Mihiel and Blanc Mont in the summer and fall of 1918. During the final push through the Argonne Forest, these French arms were replaced by American-designed Browning M1917 heavy machine guns and M1918 Browning Automatic Rifles, both in .30-’06 Sprg. However, it was Marines in the attack with their rifles and pistols who won laurels for the Corps. While Pvt. John Kelly captured German machine gun positions with his M1911 pistol, four other enlisted Marines performed feats of valor above and beyond the call of duty with their M1903 Springfield rifles, including: Cpl. John H. Pruitt (Ser. No. 171397), Sgt. Louis Cukela (Ser. No. 381782), Sgt. Matej Kocak (Ser. No. 576472) and Sgt./Maj. Ernest A. Janson, who served under the name Charles F. Hoffman (Ser. No. 606483). All five Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor.

Courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps

Another brigade of Marines was also sent to France, but plans to form an all-Marine division from the 4th and 5th Brigades did not materialize. A few replacements were issued U.S. Model 1917 rifles at Quantico and took them to France. Meanwhile, Marines at this new Quantico, Va., Marine base were training on artillery—French 75 mm field guns, British 4.5″ howitzers and even 7″ tread-mounted tractor guns—as the intended artillery component of the envisioned Marine division, but the war ended before they shipped out. In addition, Marines formed observation balloon units, while aviation units in Florida and Philadelphia prepared for service in France and in the Azores.

After the November 1918 Armistice, the Marine Corps found itself in yet another “Cacos Revolt” in Haiti, while continuing to pacify the neighboring Dominican Republic. Along with the Lewis machine gun, the new Browning Automatic Rifle played a decisive role in Haiti, but the most innovative firearm of the era, the .45 ACP Thompson submachine gun, would soon gain fame in the jungles of Nicaragua. Along with the 12-ga. pump “trench” shotguns that had been issued to selected Marines at St. Mihiel, Thompson guns were used by Marines to guard the U.S. Mail from bandits in the early 1920s (October 2025, p. 44). Their value in jungle warfare soon became apparent in the Second Nicaraguan campaign of 1927. Carried by Marines and some units of the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua, such as those led by the legendary Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, the “Tommy Gun” soon earned a niche in the Corps’ history.

Thompson submachine guns also found their way to China with Brig. Gen. Smedley D. Butler’s brigade in Shanghai that was sent to protect American interests during the fighting there between the Chinese and the Japanese. American versions of the French Renault light tank from World War I, as well as 37 mm French M1916 Puteaux infantry support guns, also saw service in China. The Marine Corps had maintained a presence in China (including the famous Mounted Detachment—“Horse Marines”—in Peking), dating back to the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion, but the “China Marines” in Shanghai were now experimenting with a new tactical approach using the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle: the development of the four-man fire team based around the BAR.

During the Guadalcanal campaign in 1942, Marine parachutists and Raiders employed some firearms, such as Reisings and Johnsons, that appeared briefly, or in very limited numbers, during World War II. The Marine parachutist seen here in “Killer” by Col. Donald Dixon, USMC, is firing a .45 ACP M55 Reising submachine gun, which was withdrawn from the Corps’ inventory by 1944. Courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps

Before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the 4th Marines had been using these teams on the streets of Shanghai, and during World War II, the Marine Corps refined this arrangement for its infantry squads, which consisted of a squad leader and three, four-man fire teams. Each team in the squad had a fire team leader, an automatic rifleman and two ammo-carrying assistants armed with rifles. After some controversy, the Marine Corps adopted the Army’s .30-cal. M1 Garand rifle, but the first division of Marines deployed to Guadalcanal in 1942 was still armed with the venerable five-shot M1903 Springfield. Subsequent units of Marines in the “island hopping” campaigns from New Georgia to Okinawa carried the M1 rifle, and they soon learned to appreciate the quick sight picture, rapid semi-automatic fire and increased magazine capacity of the eight-shot Garand. While some Marines praised the light .30-cal. M1 carbine for its handiness and large magazine capacity, others decried its underpowered cartridge’s “stopping power”—especially during a Japanese banzai attack—and opted for an improved version (M1911A1) of the venerable .45-cal. sidearm that had served in World War I and the Banana Wars.

Specialized units, such as parachute and Raider battalions, carried an array of atypical small arms—.45 ACP Reising submachine guns, .30-’06 Sprg. Johnson semi-automatic rifles and light machine guns (their designer, Melvin M. Johnson, Jr., was a Marine Reserve officer), and even .55-cal. British Boys anti-tank rifles. Most importantly, Marine snipers came into their own, using M1903 rifles with large Unertl target telescopic sights, as well as M1903A3 rifles with more conventional scopes. All the emphasis that the Corps had placed on marksmanship competitions during the preceding 40 years paid off handsomely, as Marine snipers became an important mainstay on the battlefield—a position they maintain to this day.

Besides re-organizing its infantry tactics, the Marine Corps had made great strides in the development of amphibious warfare, incorporating light and, later, medium tanks, as well as amphibian tractors in the pre-World War II period. The Defense Battalions (descendants of the Advanced Base Force units) employed 155 mm guns and anti-aircraft guns, ranging from 90 mm cannon to .50-cal. Browning machine guns. Marines in the six infantry divisions were firing 105 mm howitzers, 75 mm pack howitzers, 37 mm anti-tank guns, mortars, “bazooka” rocket launchers and .30-cal. M1919 Browning light machine guns, as well as employing flamethrowers. During the war, Marine air, with its emphasis on dive-bombing, provided much needed, and well-coordinated, close-air support to the Marines on the ground (and for Army soldiers in the Philippines), as well as supporting the Navy in its drive across the Pacific Ocean.

Gun photos all courtesy of Rock Island Auction

As early as the 1930s, the Marine Corps saw the advantages of rotary-wing aircraft and experimented with Pitcairn Autogiros in Nicaragua. At the end of World War II, however, and with the advent of the atomic bomb, the Marine Corps realized that “Vertical Envelopment”—the ability to get troops from ships over a contested beachhead or through an area infested with nuclear fallout—was the wave of the future. Accordingly, the Marine Corps embraced the helicopter that the Army had used briefly for medical evacuations toward the end of World War II and based its doctrine around it. When the Korean War broke out in the summer of 1950, Marine helicopters came into their own. Aside from an improved 3.5″ rocket launcher, the M26 “Pershing” tank, an upgraded amphibian tractor, jet aircraft and an increased use of .50-cal. machine guns in fixed positions during the later stages of the war, the Marine Corps fought the Korean War with the same infantry weapons they had used in World War II.

At the same time, the Corps was experimenting with select-fire (semi- and full-automatic) battle rifles to replace its .30-cal. M1 rifle. By the mid-1950s, the Marine Corps was following the Army’s lead in adopting the M14 select-fire rifle in 7.62 NATO. This cartridge was adopted by many of America’s allies in the “Cold War” with the Soviet Union and Communist China. The hard-hitting M14 served the Marine Corps well into the early years of the Vietnam War until being phased out in favor of the 5.56 NATO M16. The M16 had been developed by Eugene Stoner (who also had invented an entire weapons system that the Marine Corps was considering at the time), and it proved to be an excellent choice as a standard infantry arm, since its descendants are still in use today worldwide.

Whether they be troop-carrying tilt-rotor aircraft, helicopters or assault amphibian vehicles, the object of such conveyances is to get the Marine rifleman to the battlefield. Likewise, close air support and artillery fire are there to help the Marine rifleman in closing with the enemy. In the end, however, it is the Marine rifleman who wins the battle, and every Marine is a rifleman. “The Strategic Lance Corporal” by Kristopher Battles, USMC artist

While the standard pistol (M1911A1) stayed the same during Vietnam, Marines got a more modern version of the pump-action 12-ga. shotgun they had used in both world wars. The sniper rifle was also improved, with Marine snipers now using scoped Model 70 Winchesters and an upgraded version of the Model 700 Remington rifle—the M40. The M40 rifle proved its worth in the jungles of Vietnam and for many years thereafter. The M60 machine gun, also in 7.62 NATO, replaced the .30-cal. M1919 Browning a few years before the Vietnam War. Marines also used the M79 40 mm grenade launcher, later adapting a simplified version of it as an add-on underneath the barrel of their M16 rifles. By the Gulf War of 1991, Marines were armed with a new 9 mm Beretta service pistol and a new machine gun, the Belgian-designed M249 Squad Automatic Weapon. While the original M16 went through many modifications and eventually became the M4, it has now largely been replaced by the 5.56 NATO M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle, based on a Heckler & Koch design, as the standard shoulder arm in the Corps.

While maintaining the peace and halting the spread of terrorism into the 21st century, the Marine Corps does not look the same as it did in bygone eras. Technology has improved greatly and has afforded Marines an edge over their adversaries on the battlefield. However, in the end, all these innovations, like helicopters, tilt-rotor transports, amphibian assault tracked vehicles, jet aircraft and the like have emerged for one reason: To get the Marine with a rifle to the front of the fight and provide air and artillery support for that Marine in the assault. After all, every Marine is still a rifleman.

Editor’s Note: A frequent contributor to American Rifleman magazine, and a commentator on “American Rifleman Television” for decades, Ken Smith-Christmas served on the staff of the Marine Corps Museum for nearly 30 years and retired from the National Museum of the U.S. Army’s Planning Office as its Director of Exhibits and Collections in 2010. The wholehearted support of the staff of the National Museum of the Marine Corps in the preparation of this article is deeply appreciated.

Read the full article here