The Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) is one of the most hotly debated military firearms in American history. John Moses Browning’s genius design from 1918 still has the power to evoke powerful emotions from small arms reviewers. Working with the editors at American Rifleman, I’ve assembled a group of comments from the troops who used in combat from World War I until the Korean War.

A Machine Rifle Debut

John Browning originally conceived his automatic rifle during 1910. The “machine rifle” design generally went unnoticed until America’s entry into World War I seemed inevitable. On Feb. 27, 1917, Browning demonstrated the early “Browning Machine Rifle” at Congress Heights, located just south of Washington, D.C. Several hundred members of Congress, the U.S. military, and the press were on hand to see the fledgling BAR and Browning’s water-cooled machine gun (later designated the M1917). Also present were representatives of the French and British military—everyone was suitably impressed, particularly with the big automatic rifle.

The live-fire demonstration worked so well that Browning was awarded a contract within weeks. Unfortunately, production of the BAR didn’t begin until February 1918, and even then, early manufacturing issues meant that the rifles weren’t produced at full capacity at Winchester until June. By July, the BARs began to trickle into France but were not used in combat until mid-September. The greatest use of the BAR in World War I came during the Argonne offensive of October—November. Even though the BAR saw little more than a month’s combat service in any appreciable numbers, it left an indelible impression on both friend and foe.

From the General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces came this entry titled Notes on recent operations, November 1918:

Automatic Rifles: “One division equipped with light Browning automatic rifles used only eight rifles per company and kept eight in reserve. While this is good practice with the Chauchat, it is not expedient with the Browning. The Chauchat, owing to its weight and inaccuracy, is chiefly valuable during the consolidation. The Browning, on the other hand, is practically as mobile as the ordinary rifle and possesses approximately the same accuracy. These qualities, together with its great firepower, make it imperative that the maximum number should be employed in the fight.”

There was little time to develop specific tactics for the BAR in late 1918, but it was soon apparent that the firearm delivered a level of man-portable mobile firepower previously unknown to the infantry. One stateside notion about BAR tactics was quickly dispelled in France—the use of a specially designed cup on the gunner’s belt to hold the butt of the big automatic rifle while the gunner engaged in the practice of “marching fire.” Even though it was practiced, the tactical conditions in France made this technique laughable, if not suicidal.

The Doughboys knew a good thing when they saw one. Corporal Jack Thomas of the 36th Division wrote in early November 1918:

“The most interesting thing I saw in the fight was the bringing down of a Boche plane with a Browning Automatic Rifle. I believe this little gun to be the finest of its kind in existence.”

Corporal R. A. Herbst, also of the 36th Division, discussed his unit’s use of the BAR in November 1918:

“We were the only ones that used the Browning Machine Rifle in battle. It worked wonderfully. The Germans, having never seen or heard of this rifle, were scared to death, and we captured many prisoners.”

In “America’s Munitions 1917-1918,” the report of Benedict Growell, the assistant secretary of war, director of munitions stated:

“The Browning automatic rifles were also highly praised by our officers who had the chance to use them. Although these guns received hard usage, being on the front for days at a time in the rain and when the gunners had little opportunity to clean them, they invariably functioned well.”

On November 11 we had built 52,238 Browning automatic rifles in this country. We had bought 29,000 Chauchats from the French. Without providing replacement guns or reserves, this was a sufficient number to equip over 100 divisions with 768 guns to the division. This meant light machine guns enough for a field army of 3,500,000 men. In heavy machine guns at the signing of the armistice we had 3,340 of the Hotchkiss make, 9,237 Vickers, and 41,804 Brownings, or a total of 54,627 heavy machine guns, enough to equip the 200 divisions of an army of 7,000,000 men, not figuring in reserve weapons.”

Reimagined As Light Machine Gun

Just a few years after World War I, infantry formations around the world were clamoring for light machine gun designs. The U.S. military began the same investigations, but most of their focus was on re-configuring the BAR. Browning’s original design created a full-sizedautomatic rifle (.30-06), with the emphasis on “rifle.” The M1918 model was a big rifle—47″ long and weighing 16 lbs. Its cyclic rate is up to 650 rounds per minute. By World War I standards, the BAR was other-worldly in its capabilities. And while it is true that the soldiers of the era were generally smaller than we are now, their complaints were smaller, too. Gripes about its weight disappeared when troops saw the rifle’s tremendous firepower in action.

What’s In A Name?

During the 1920s, the global shift towards light machine gun designs led many to assume that was the role the BAR was intended for or could be easily adapted to.

For the BAR, this strange modification journey began in 1920, as the U.S. Cavalry sought a far more portable machine gun. At first, much of the BAR’s modifications seemed to be weighted more in semantics than anything else. The Cavalry’s modified “automatic rifle” was described as the “Browning machine rifle, Model of 1920” (and later re-designated as Browning machine rifle, Model of 1922).

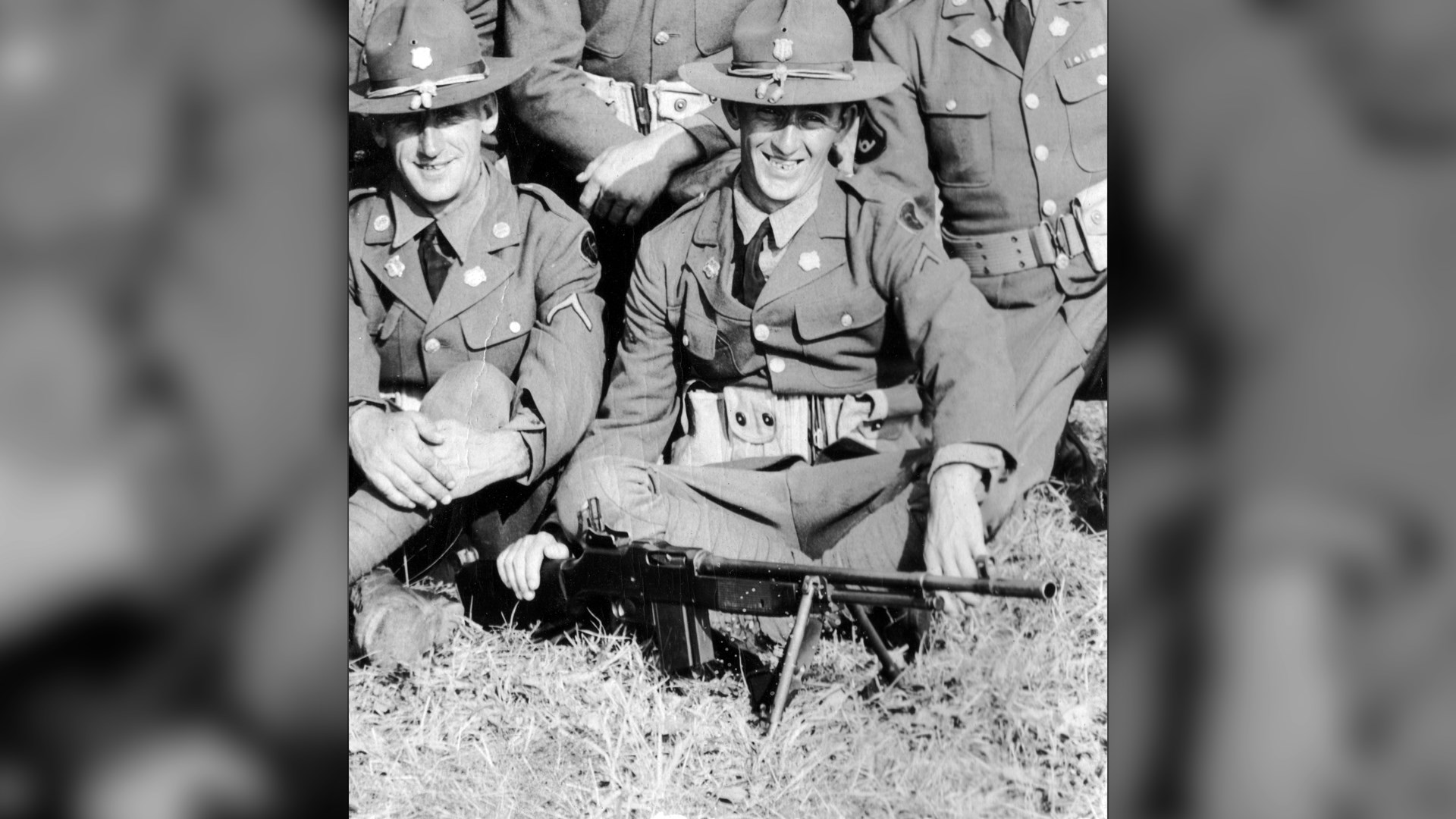

Whether a machine rifle or automatic rifle, the Cav’s Browning now featured a bipod, and those two spindly metal legs would have a big influence on the BAR for the rest of its service life. Despite an increase in weight to about 20 pounds, the U.S. Cavalry was very excited about their BAR variation, and they described this in a report to the Chief of Ordnance on May 5, 1920:

“The automatic rifle, which has given quite general satisfaction, has not been satisfactory in all particulars. It is too heavy to be used readily as a shoulder weapon, and, not having a bipod mount, was not sufficiently stable for accurate fire when used as a single shot weapon, on account of the difficulty of holding the aim when the piece was fired, due to the action of the breech mechanism moving forward when the trigger was pulled. Furthermore, it was not capable of sustained fire to any great extent, as it readily becomes overheated. In the opinion of the Board, a weapon capable of a greater sustained fire than the automatic rifle, and yet a weapon more mobile than the machine gun, was required with the infantry assaulting lines.”

“It was also believed that if such a weapon could be secured that would fulfill the functions required of the machine gun with the front line, it would leave the machine gun freer to fulfill its important role of overhead fire, both direct and indirect. Experience in the late war showed plainly that when machine gun companies were assigned to the assaulting lines they often failed to keep up with those lines, due to lack of mobility, difficult terrain, and for other reasons. In their attempt to do so, they were no longer available for use in overhead fire. A distinct advantage the machine rifle will have over the machine gun as a frontline weapon is that the machine rifle, in its operation, as to visibility, will resemble the automatic rifle, and not be readily distinguished from the infantry line. It, being handled by one man with the only other man necessarily in his immediate vicinity, will not be easily distinguishable from any other rifleman.”

There are some big contradictions in that report, and quite a bit of imagination that the BAR would become more of a machine gun simply by adding a bipod. The report does not discuss the inherent limitations of the BAR barrel in sustained fire situations—that is a problem for light automatic weapons that has only been somewhat solved by using a quick-change barrel, and an easily changed barrel was never a feature of the BAR. Finally, the BAR was never issued with a magazine larger than 20 rounds for infantry combat. A few experimental 40-round magazines were produced for anti-aircraft use, but the concept quickly disappeared. The Infantry and Cavalry Board had ideas on this issue as well:

“The Board believes that a 30-round magazine will be more suitable for this rifle than either a 20 or 40-round magazine. The 20-round magazine does not hold sufficient cartridges for continuous fire and a greater number of magazines are required. The 40-round magazine is large, cumbersome, frail and not easily packed.”

On this, we can all agree, but ultimately there were no 30-round magazines issued for use with the BAR.

As World War II approached, the BAR was modified as the M1918A2 and received a folding bipod with skid-type feet, a firing-rate reducer (designed by Springfield Armory) mounted in the buttstock and offering two rates of fire (slow/fast automatic), a smaller flash suppressor, adjustable sights, a heat shield on the barrel and a monopod stock rest. During World War II, a carrying handle was attached to the barrel. The BAR’s weight (unloaded) climbed to 20 lbs.

World War II

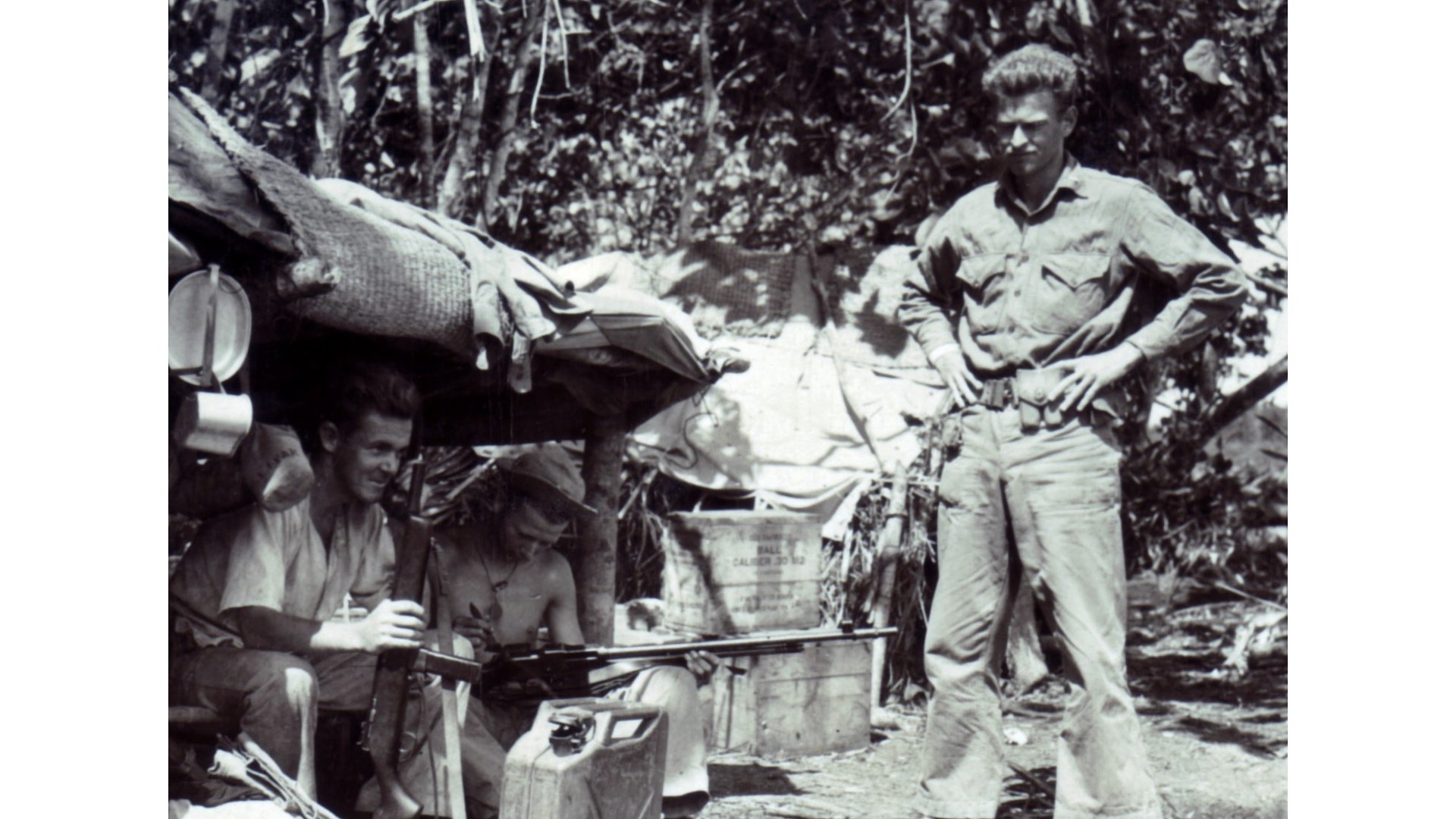

“This BAR I have here is my best friend.”—U.S. Marine Corps gunner, Guadalcanal, December 1942

From the M1918A2 manual: “The Browning automatic rifle, caliber .30, M1918A2, is not capable of semiautomatic fire. There are two cyclic rates of full automatic fire, normal and slow, which may be selected by the firer. The normal cyclic rate is approximately 550 rounds per minute; the slow cyclic rate is approximately 350 rounds per minute. The effective rate of fire for this weapon is from 120 to 150 rounds per minute.”

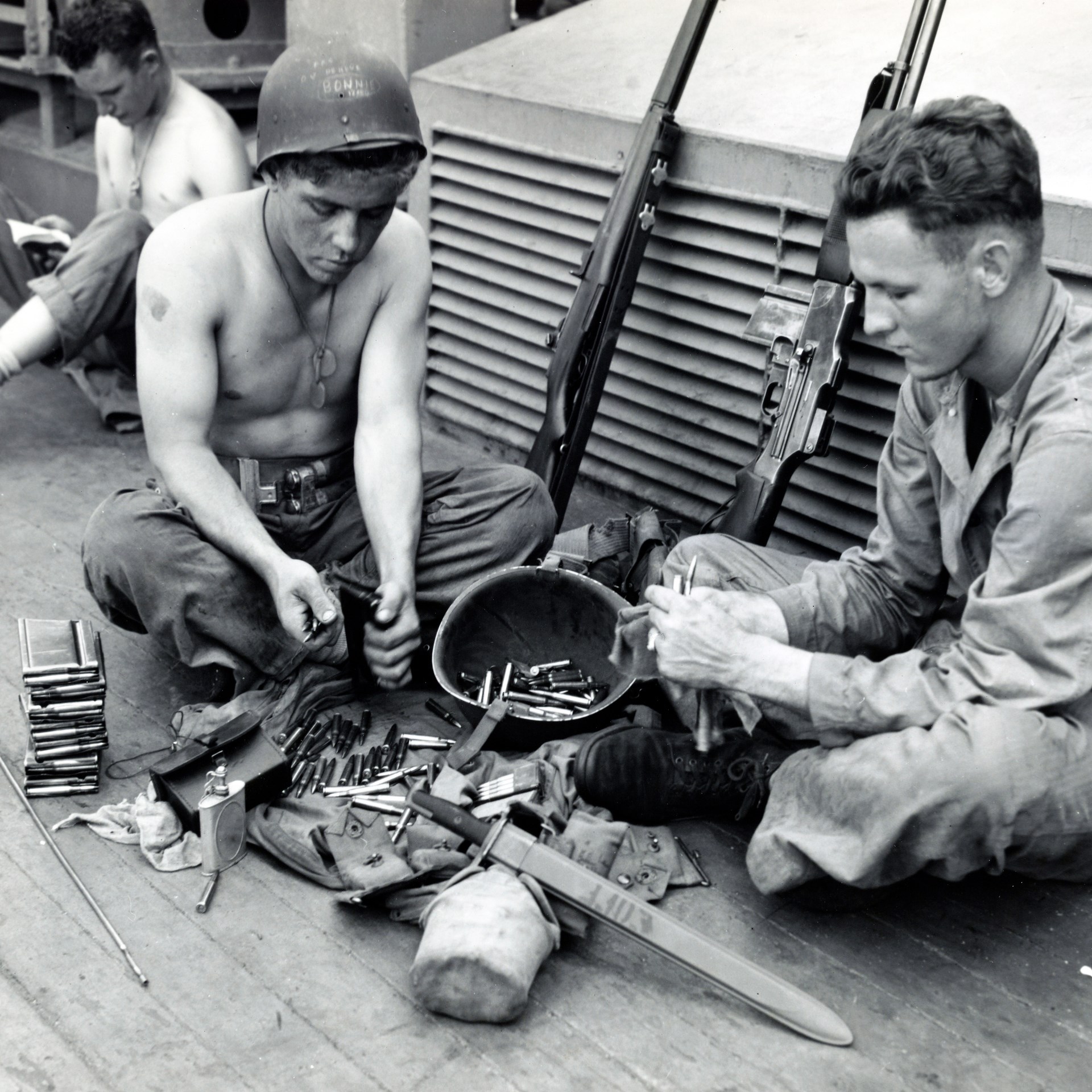

The U.S. military entered World War II with a wide range of automatic firearms—from the Browning .50-cal. M2 heavy machine gun to the water-cooled Browning M1917A1 .30-cal. machine gun, the air-cooled Browning M1919A4 .30-cal. machine gun and the .30-cal. Browning Automatic Rifle. All of them were deadly, but there are times that the BAR appears to be misunderstood. One thing is clear, however—once in combat, a great many BAR men removed the “extra parts” added to the gun to save weight.

BAR gunners received specific training on the use and care of the big Browning automatic rifle, but it seems that few other infantrymen knew anything about the platform. The need for BAR training for a majority of squad members is a consistent theme throughout the war, but it never seems to have properly addressed:

“It is important that the entire squad know the BAR. Not just two men. Reason: think of the BAR men who are wounded, get killed, and become sick and must be evacuated.”

U.S.M.C. Notes on Jungle Warfare from Guadalcanal, December 1942

“It was found in combat operations that men lacked sufficient knowledge of weapons other than the one with which they were armed. A general lack of familiarity with the Bazooka, rifle grenade and BAR was prevalent. On occasions squads were without a BAR due to casualties and the lack of ability of other members of the squad to take over and man the weapon.”

“It was agreed that all infantry soldiers should be thoroughly trained in the use of this important weapon.”

Operations in the Italian Campaign, 1943-1945

“With the inevitable early combat casualties, it is rarely possible to man 3 BARs with EXPERT BAR men. Few Marines ever become expert in this weapon, and when this weapon is in the hands of inexperienced men, several malfunctions and jams occur unnecessarily. It is better to have two good BAR men per squad than many poor ones.”

The 4th Marine Division report from Iwo Jima 1945

More BARs Please

Throughout World War II, in all combat theaters of operation, the troops regularly asked for more BARs. And as the war went on, they tended to get them. Even a casual review of combat photos shows many more BARs in Marine Corps service in 1945 than at any time before. However, a report from the 4th Marine Division on Okinawa recommends going with less BARs but more qualified gunners, as well as adding a scout/sniper group.

“BAR and rifle squad: It is recommended that the number of BARs in the rifle squad be reduced from three to two (six per platoon). It is suggested that a rifle squad contain a squad leader and three fire groups of four men each.”

“Two of the fire groups to remain as they are now with a BAR. The third fire group to be a scout group, the leader being second in command of the squad. The other three men of the group should be trained as scouts and snipers, equipped with M1 rifles or M1903s with telescopic sights, Two BAR’S furbish sufficient fire power for a rifle squad.”

In their report on the fighting on Bougainville, the Americal Division made their case for more BARs, along with a healthy dose of fire discipline:

“To increase the volume of automatic fire, additional BARs should be provided on the basis of at least two (2), and preferably three (3) per squad. The problem of carrying sufficient ammunition for these weapons is difficult; consequently, fire discipline within the unit must be stringent, and the automatic weapons employed sensibly, economically, and only when the situation so demands. A man with an automatic weapon in his hands tends to fire the weapon at its maximum rate. This tendency must, and can, be curbed by proper training.”

The 93rd Infantry Division found extra BARs to be useful for jungle patrols on Bougainville:

“It was found that three BARs per squad was not excessive on patrols. On the offense the BARs should be well in front and should open up as soon as contact is made. This provides an excellent base of fire for each squad.”

For the men of the 82nd Chemical Battalion, the BAR was the only automatic firearm they had:

“Browning Automatic Rifles are the only automatic weapons authorized for this organization, and these were used extensively. In the defense they were placed on the flanks of the mortar position and were prepared to give protective fire along the barbed wire entanglements to the front and rear. BAR positions were protected by riflemen 5-10 yards distant, and one rifleman was assigned to each BAR position. On the march, BARs were placed at the head of the column and one at the rear. Company headquarters BAR personnel were attached to platoons when the situation demanded it. More automatic weapons are necessary for adequate protection.”

Indispensable In The Jungle

When the thick undergrowth prevented the quick deployment of Browning machine guns, the BAR was right there with the riflemen to provide a fast-moving, hard-hitting base of fire. The 43rd Infantry Division noted their experience with the BAR on Munda: “The BAR has high jungle mobility and firepower. Some of its uses are to reinforce the final protective fires at night, to establish trail blocks and to destroy snipers.”

The Fourth Marines praised the BAR’s capabilities during the campaign on Saipan: “Indispensable in Saipan in offense and halts. Rifles with the bipod are preferred.” (Note: this is the only time I’ve ever seen a stated preference for BARs with bipods. Much of the time, the gunners threw them away.)

The XIV Corps report from Bougainville stated simply: “The BAR is indispensable.”

Blasting Nazis Out Of Hedgerows & The Rest Of Europe

The BAR did its same deadly work in Europe and the Mediterranean. Soon after D-Day, US troops found themselves fighting in the hedgerows of Normandy, and the BAR quickly established itself as a prime small arm to hammer the Germans out of their Bocage positions.

“I recommend two BAR teams and an additional Tommy gun to a squad for hedgerow fighting.”—Platoon Leader, 79th Infantry Div.

“Heavy automatic fire, especially from BARs, is the best way to flush out hedgerows.” —Company Commander, 12th Infantry Regiment

Meanwhile, the BAR’s combination of mobility and firepower bedeviled the Germans as much as it did the Japanese:

“For a while the Germans thought our BAR was a machine gun, but by the time they brought fire on the BAR position the gunner had moved and was firing on them from another direction.” —Via Combat Lessons #5

“The Browning Automatic Rifle was found to be invaluable in the attack because of its mobility and fire power, and patrols sent out were always reinforced with automatic rifle teams.” —Via Combat Lessons #2 Italy

Wherever they fought, most BAR gunners sought to return their automatic rifle to its original 1918 configuration—a big damn gun that fires fast and tears the hell out of the enemy. It doesn’t need a bipod or a carrying handle or a shoulder rest. All that it requires is a brave American to use it and an enemy to stand in its way. The following comment from “Operations in the Italian Campaign 1943-1945” sums up the Browning Automatic Rifle quite well:

“The BAR has proved an excellent weapon and needs no modification. There were no complaints as to its mechanical functioning and very few stoppages were reported. Most officers suggested adding 6 more BARs to the Company without adding to the number of magazines per BAR team.”

“Many suggested leaving off the bipod to save weight, figuring that in a defensive situation, when the bipod is of greatest value, machine guns (lights or heavies) could be brought up to provide defensive fires. The LMG with bipod and shoulder rest (the Browning M1919A6) was considered excellent but should not replace the BAR, whose firepower is ample if handled by a man who really knows how to use it. The BAR was unanimously acknowledged to be the backbone of the infantry squad. Related experiences of junior officers and NCOs indicated that the Germans also held this view. In all infantry engagements the enemy constantly gave priority attention to the BAR in the squad. The BAR was credited with the disruption of many enemy counterattacks.”

As a personal note, I would highly recommend that if you get a chance to fire a BAR, make sure you do it. Put it on your bucket list. The BAR looks big and heavy, because it is, but once you bring it to your shoulder, you realize that it is exactly the right size, and it is exceptionally well-balanced. Torch it off on full-automatic, and you will feel superhuman.

Read the full article here